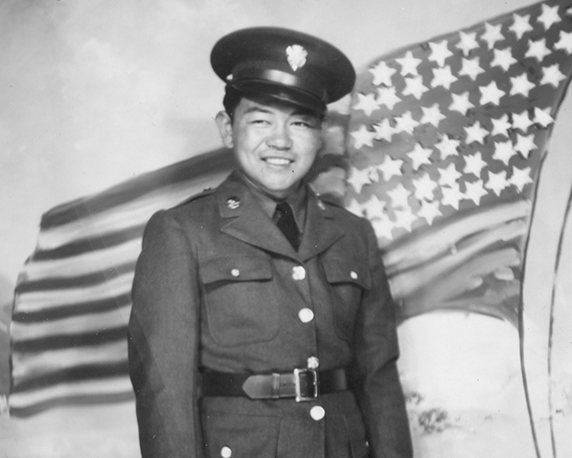

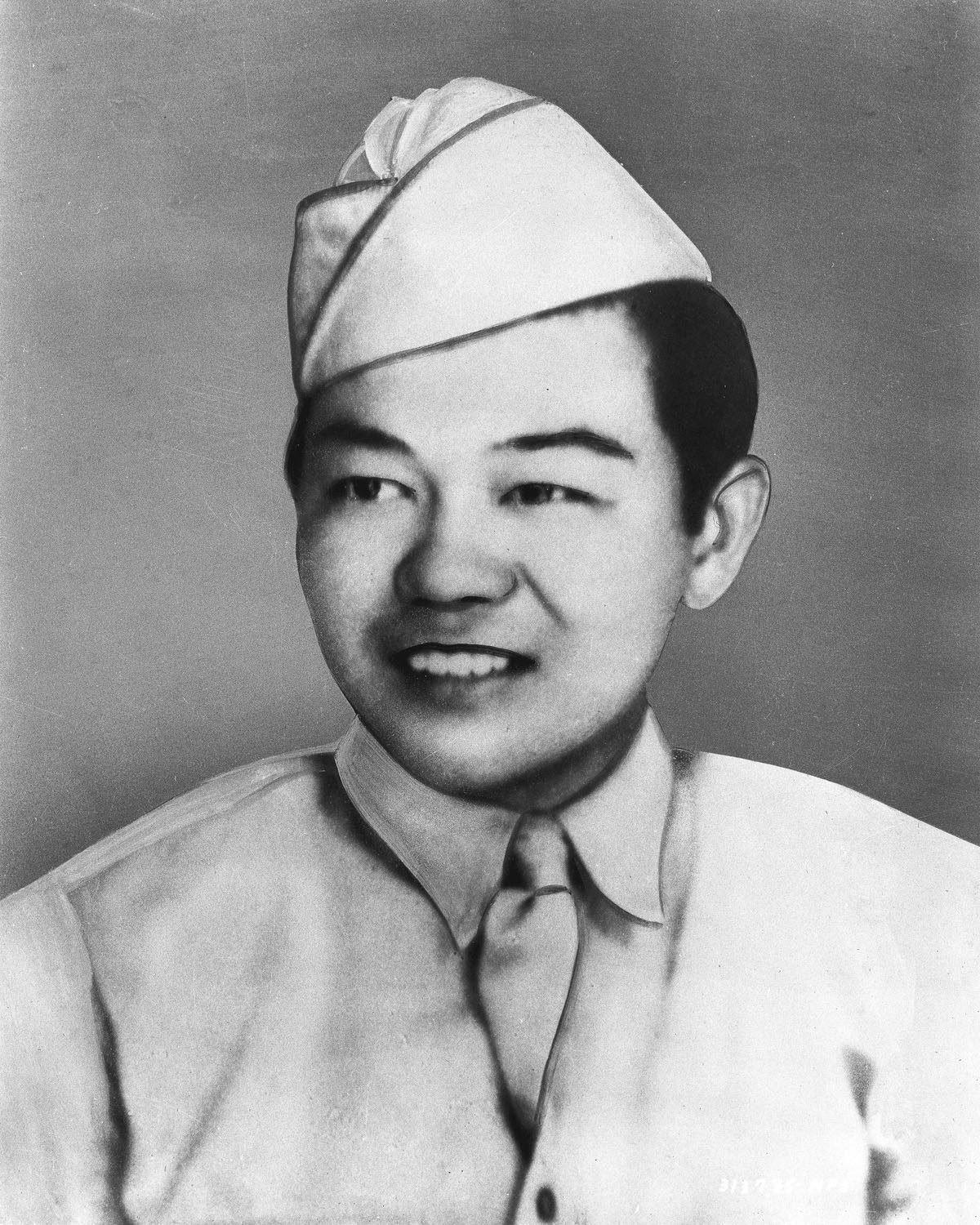

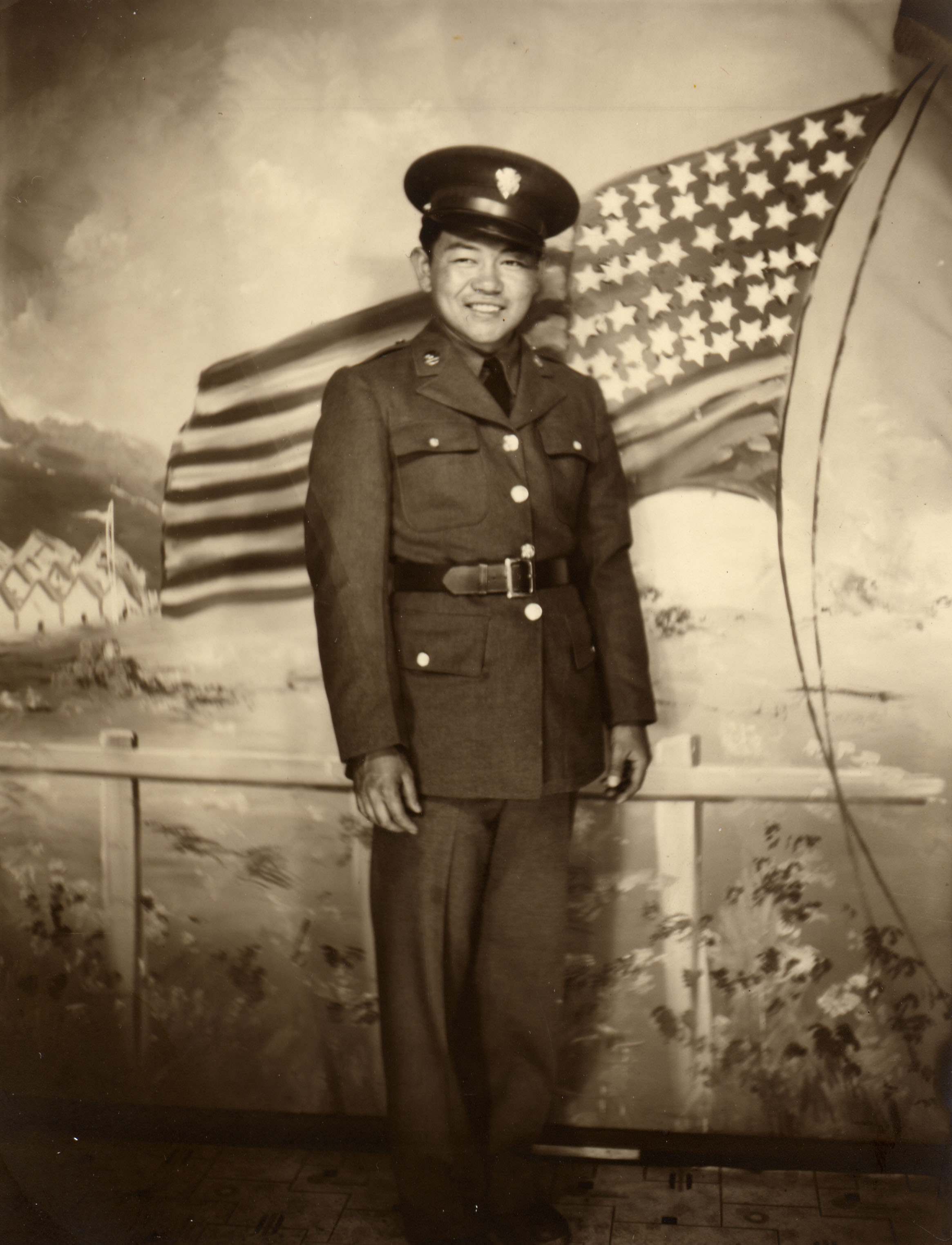

Private First Class

Sadao Munemori

Company A

100th Infantry Battalion

1922 - 1945

- Citizenship

- Compassion

- Courage

- Sacrifice

Legacy of Valor

Sadao Munemori was the first Japanese American to be awarded the Medal of Honor, the US military’s highest medal of valor.

Sadao made the ultimate sacrifice for his country in saving the lives of his fellow soldiers.Sadao was very close to his family, especially his widowed mother, Nawa. Born in Los Angeles, he was the fourth of five children. His nickname was Spud because he preferred potatoes to rice when he was young.

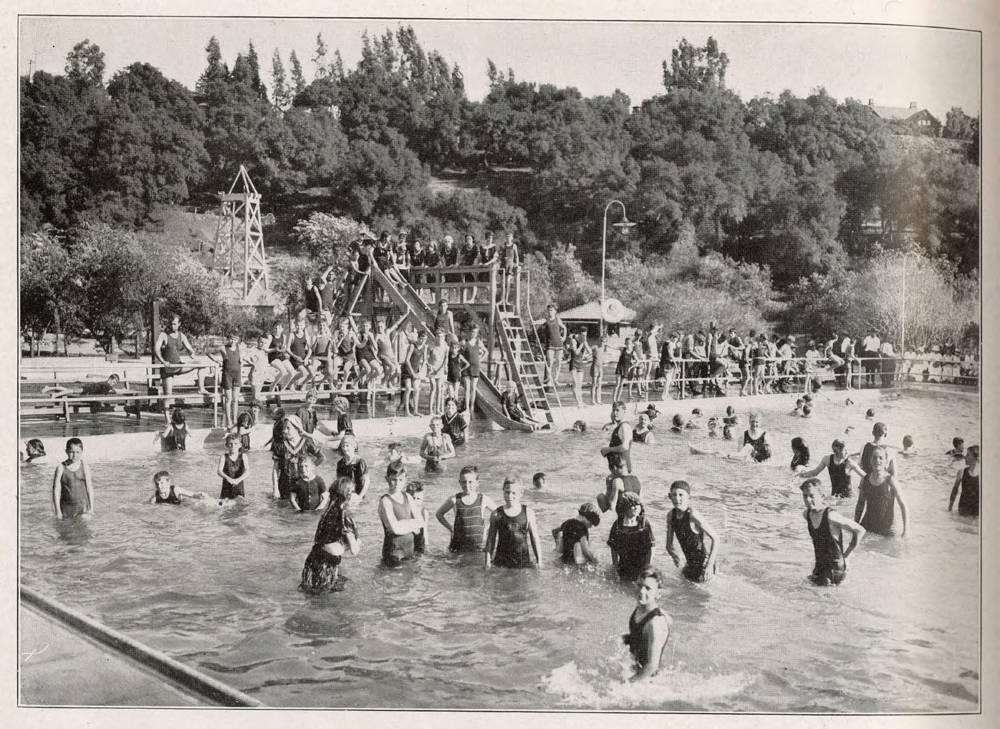

He also liked to swim. As a teenager, he went to a local public swimming pool, but was turned away because he was Japanese.

Brookside Park swimming pool

As a boy, Sadao had great ambitions. After losing an argument with his older sister, Yaeko, he said, “You just wait. When I grow up, they’re going to name a ship after me.”

After graduating from high school in 1940, he worked as a mechanic. At age 19 he enlisted in the US Army on November 2, 1941. A month later, Pearl Harbor was bombed and the US officially entered World War II.

I think I did right by enlisting because my home is here in the US and it helped a lot to bind the family together more than ever.|Sadao in a letter to his sister Kikuyo “Keech”|January 2, 1944

Easter card sent to the Munemori family from Camp Robinson, March 28, 1942

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which

allowed for the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Sadao’s

family was eventually sent to Manzanar, one of ten concentration camps in the

nation’s interior. Manzanar was located in the Owens Valley in the Sierra

mountains in California.

In November 1942, Sadao was selected for the Military Intelligence Service language

school at Camp Savage, Minnesota.

I got insurance. ... If I get killed after May 1 '42 Mom will get $80.00 a month for the rest of her life. ... I know I’ll come back from the war alive, but just in case they send you my ‘dog tag.'|Sadao in a letter to his sister Kikuyo|March 1942

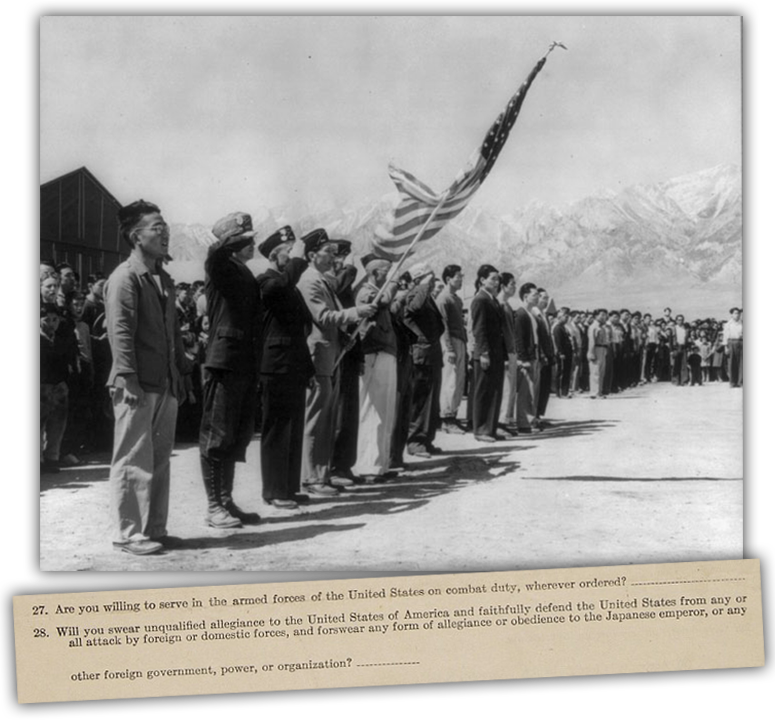

Top: American Legion and Boy Scouts on Memorial Day at Manzanar; Bottom: Questions from the "loyalty questionnaire."

About two-thirds of all Japanese Americans incarcerated at Manzanar were Nisei, American citizens by birth. The rest were immigrants, like Sadao’s mother, who had lived in the US for decades but were legally barred from citizenship.

Frustration and anger came to a boiling point in December 1942 when two Japanese Americans were killed and 10 were wounded by military police during the “Manzanar Riot.” Tensions intensified in 1943 when the imprisoned were forced to answer a “loyalty questionnaire” behind barbed wire.

When the 442nd RCT was created for Nisei infantrymen, Sadao decided to transfer from the Military Intelligence Service to avoid fighting in the Pacific. He knew that his elder sister’s husband had been drafted and was serving in the Japanese army. To make this change, he had to accept a lower rank of private from technical sergeant.

Sadao was able to visit his family in Manzanar before he was sent to boot camp in Mississippi in May 1943. His beloved mother, Nawa, hung a Blue Star flag in her barracks to show that she had a son serving in the war. Sadao, in turn, brought his mother’s photo with him during his military service.

Tell Mom I’m always thinking of her and I’ve got her picture right on top of my shelf looking down at me.|Sadao to his sister Kikuyo|November 25, 1943, Camp Shelby, Mississippi

This blurry image is the only photo of Sadao’s visit in May 1943.

Soldiers carrying the standards of Companies A, B, C, and D of the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regiment, 34th Division

100th Infantry Battalion

In 1944 Sadao was sent to Italy as a replacement soldier for the all-Nisei 100th Infantry Battalion, which had been formed in 1942. As part of the 100th Battalion, Sadao would engage in fierce battles on the European front. He fought in the Rome-Arno Campaign and then helped to rescue the Lost Battalion in the Vosges Mountains in France. During this time, he often wrote letters to his sister Kikuyo. "I had a couple of close calls with fate, but I guess it wasn’t time for me to go see Pop!" —June 9, 1944, Rome, Italy

This war is hell and it’s no place for anybody to be. I never knew I could pray so darn seriously until they started shelling holy hell out of us one day. One time the guys in a hole a few yards away got it and just missed us.|Sadao to his sister Kikuyo

'We are still not certain if the Japanese will be allowed to return to the coast, so I’d start thinking of the future."

"You would never know how much punishment a human body can endure, until you have gone through this hell."

"Just say a small prayer for me every now and then and keep your fingers crossed. Give my love to Mom for me."

—Letters from Sadao, June through October, 1944.

Gothic Line Campaign

In April 1945, Sadao, as a member of the 100th Battalion, had a new mission: to penetrate the Gothic Line in the peaks of the Apennines Mountains in northern Italy. This was the final main German defensive line, which had foiled Allied Forces for several months.

The soldiers of the 100th Battalion were to travel under cover of night to make a surprise dawn offensive. They attacked eastward to squeeze the Germans between two battalions.

The Gothic Line had sheer cliffs, some towering over three thousand feet high.

During this offensive, Sadao’s unit was pummeled by enemy fire, wounding the squad leader. Sadao took command. He ran forward through the gunfire and lobbed grenades at two machine-gun nests, effectively destroying them.

Through a shower of enemy grenades, Sadao sought refuge in a shell crater where two of his men, Akira Shishido and Jim Oda, were taking cover. An unexploded grenade bounced off his helmet and rolled toward his helpless comrades.

He dived on top of the grenade to smother the blast with his own body, saving the lives of his fellow soldiers. His company eventually was successful in its advance.

Family in the US

Back in the US, Sadao’s family had been hoping for the best. His mother, Nawa, had a dream that Sadao was lying on a snow-covered peak—not dead, but alive.

Unfortunately they received a telegram that Sadao had been killed in action in Italy on April 5, 1945.

Later Nawa would find her photo, blood-stained from the battlefield, among her fallen son’s personal belongings.

Handmade Pipe Box holding the blue star banner

Inconsolable, Nawa removed the Blue Star flag from her barracks in Manzanar and placed it in a pipe box.

A memorial service was held at Manzanar for both Sadao and another Nisei killed in action, Kiyoshi Nakasaki.

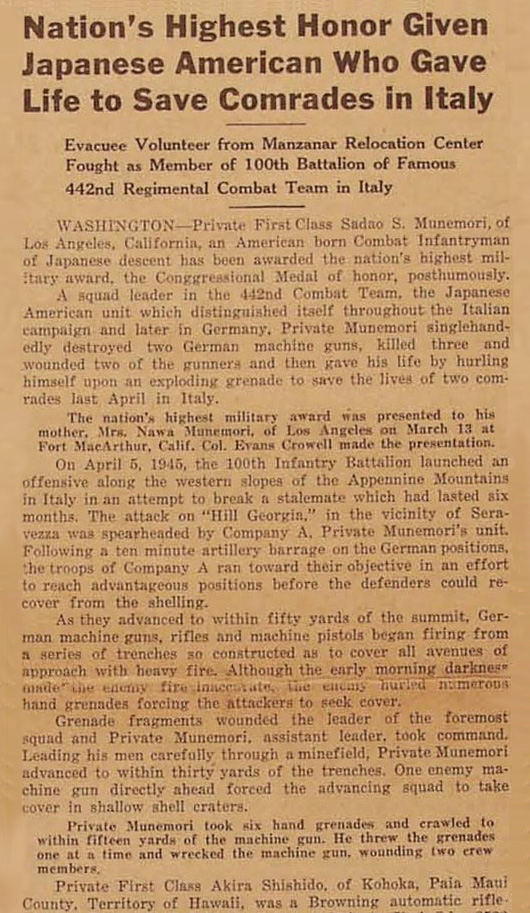

Medal of Honor

Sadao Munemori was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on March 13, 1946. It was presented to Nawa at Fort MacArthur, where her son had begun his military service.

At the time, Sadao was the only Nisei soldier from World War II to be recognized with this highest honor. More than fifty years later, 20 other Nisei soldiers would be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Pacific Citizen Vol. 22, No. 11, March 16, 1946

Sadao’s mother, Nawa, stands in front of the monument at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Post-War

Sadao is not only remembered by the awarding of the Medal of Honor.

He lives on through the naming of a Los Angeles freeway interchange, a statue in Pietrasanta, Italy, and a monument at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Most notably, true to his childhood proclamation, a troop ship was named the USNS Private Sadao S. Munemori. Years later, his sister Yaeko would stand on the deck of that ship, named after her brother in honor of his service and sacrifice.

Resources

To learn more about Sadao Munemori, visit Resources.

Credits

Photographs courtesy of the Wachtel, Yokoyama, and Munemori families, Densho, the National Japanese American Historical Society, and the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History,