Life in American Concentration Camps

What would you do if your government—even the president—wanted to

remove you and your family from your home, claiming your national ancestry was a

threat to national security?

Would you fight the decision, or would try to prove that you were loyal to your country?

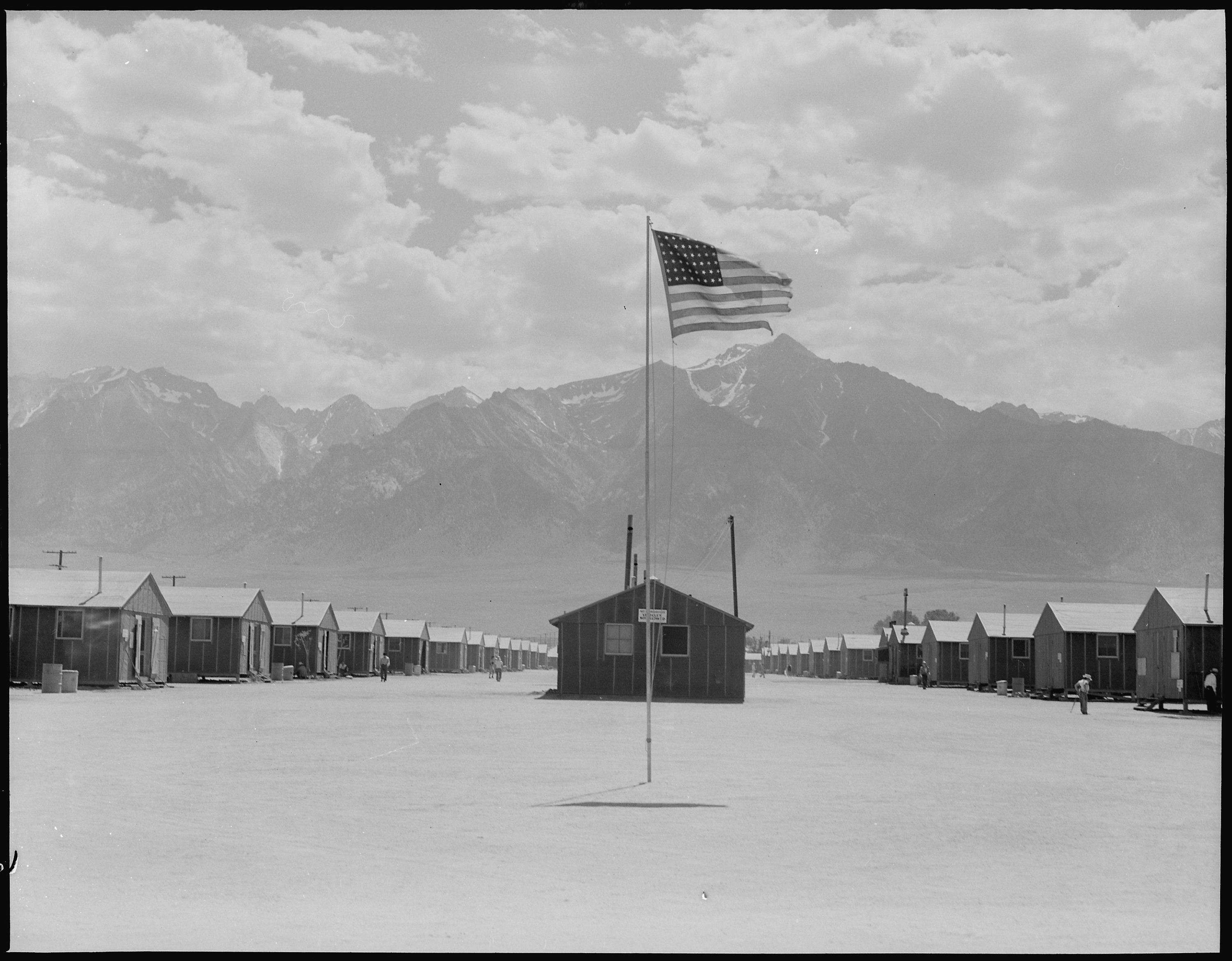

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which allowed for the mass incarceration of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Western Defense Command created a military exclusion zone along the West Coast of the United States. Every person of Japanese ancestry who lived within that zone was under curfew and eventually had to leave or be removed.

Japanese immigrants could not become US citizens. There were no elected representatives of Japanese ancestry. Laws were continually introduced to limit their success in farming and fishing.

All national organizations, except for the religious Quakers, abandoned Japanese Americans. There seemed little choice but to sell their belongings and leave their homes

Anti-Japanese sign posted on the entrance to a hotel

Supreme Court Cases

Not all agreed to comply with the curfew or presidential order.

Three young Nisei men, Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Min Yasui, living in different parts of the West Coast, refused to abide by the order under constitutional grounds.

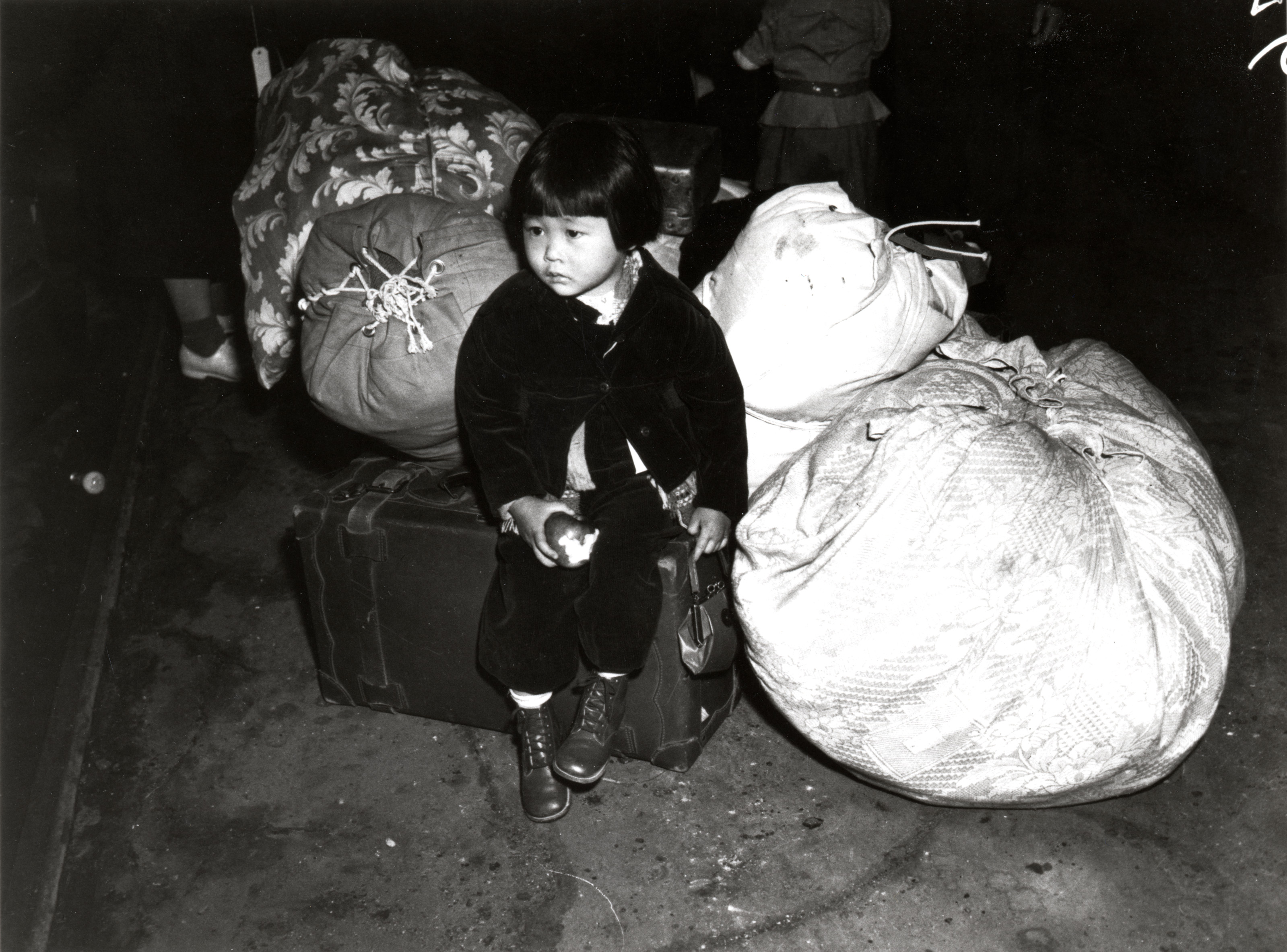

What would you have done?Ten American concentration camps under the War Relocation Authority were created in deserts and swamplands to hold the families. They could only bring what they could carry.

In the beginning, people had to live in unfinished barracks with only blankets to divide the space. The bathrooms were open with no doors.

Instead of eating together around a dining table, families had to eat in mess halls every day.

Loyalty Questionnaire

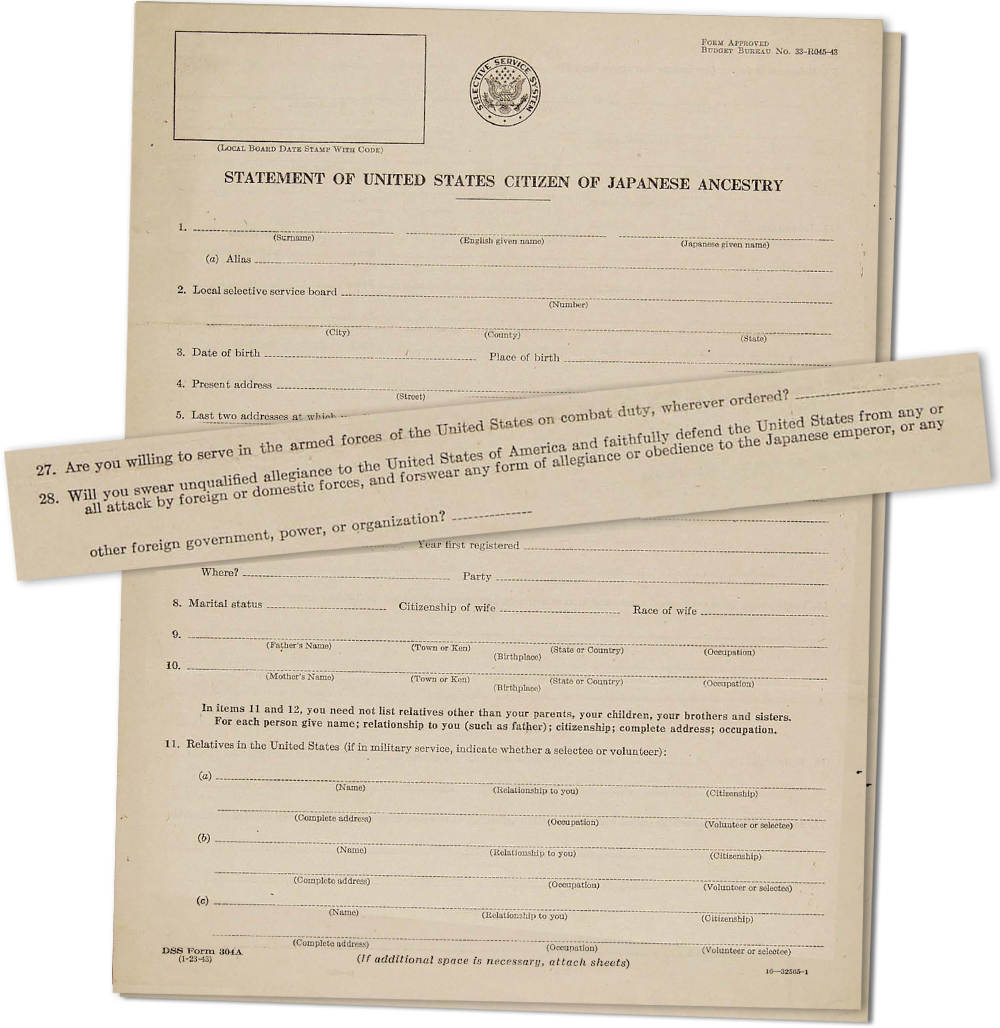

Under these circumstances, the government imposed a loyalty questionnaire on every incarcerated adult.

Two questions divided the community:

Question 27:

Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

Question 28:

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power or organization (earlier 1943 version).

Loyalty Questionnaire

Segregated Japanese Americans arriving at Tule Lake concentration camp, 1943

Some people were incensed. Why should they agree to foreswear any loyalty to the Emperor of Japan when they never held any feelings like that in the first place? And what was the segegrated military unit they kept hearing rumors about?

A total of 6,700 out of 75,000 decided to answer “no, no” to those two questions. They eventually were segregated at the Tule Lake concentration camp in Northern California.

Enlistment in the US Army

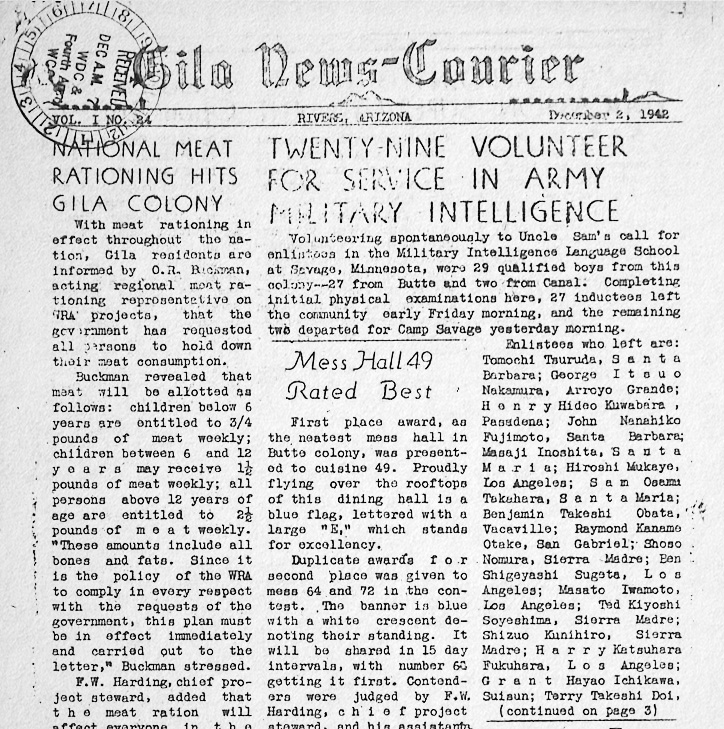

In 1943, Japanese Americans were finally eligible to serve in the US military. Some young men couldn’t wait to enlist. By the end of World War II, nearly 33,000 enlisted in the US Army including the Occupation of Japan. Many volunteered from the camp to prove their loyalty to America while they left loved ones behind—under armed guards and behind barbed wire fences.

In 1944, Nisei, like other American men, were eligible to be drafted under the Selective Service.

Gila River Courier announces “Twenty-nine Volunteer for Service in Army Military Intelligence.” December 2, 1942

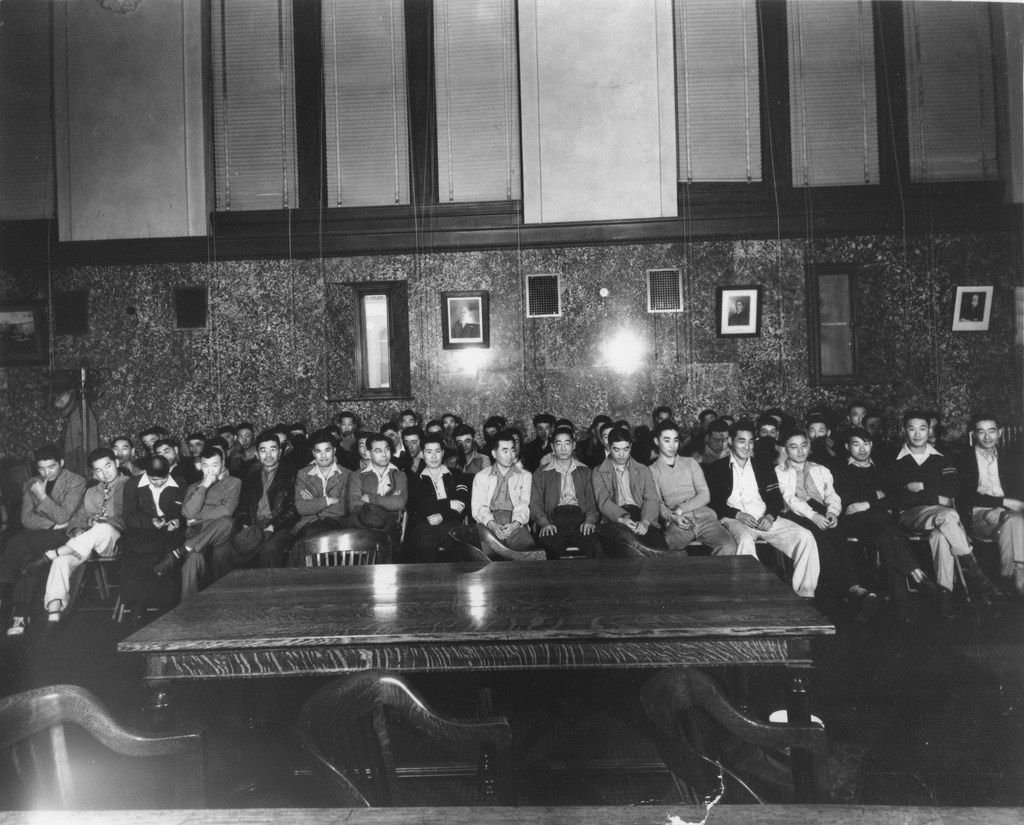

The first day of the trial of the 63 Heart Mountain draft resisters at the Federal District Court of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Resisters

Some didn’t feel that the government should draft Japanese Americans imprisoned behind barbed wire. Three hundred Nisei resisted Selective Service orders in eight of the ten camps.

Stating that incarceration was unconstitutional, the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee said that they would not fight in the US Army unless their civil rights were restored.

63 draft resisters – aside from the 27 in the Tule Lake concentration camp– were tried, convicted, and sent to federal penitentiaries.

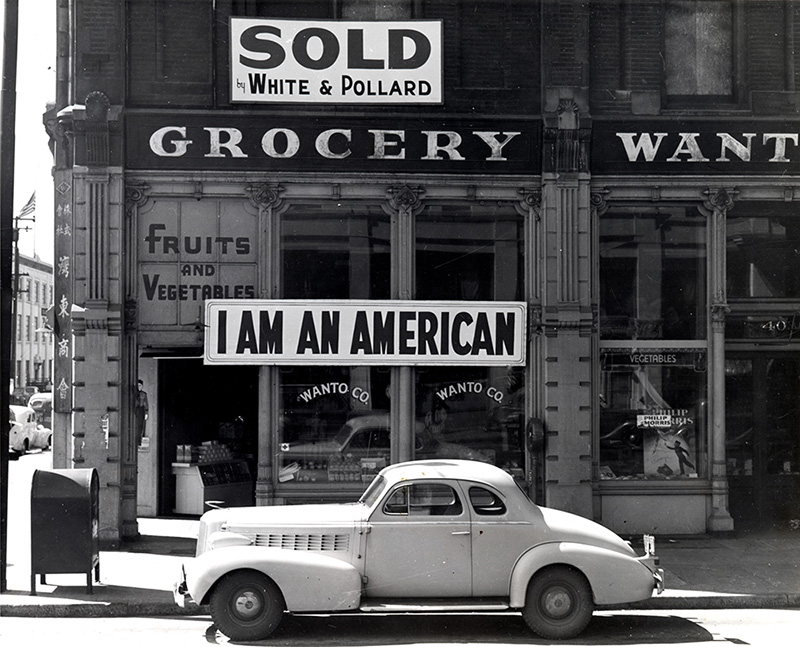

Japanese American business owner posts sign “I am an American”

What would you do if your government put you in an American concentration camp and then said that you had to fight on behalf of the same government?

Would you fight to show your allegiance on behalf of your family and community? Or would you resist the draft?

When Nisei men and women were leaving camp for the military service, the mothers of the soldiers placed Blue Stars on the windows of their barracks as Sadao Munemori's mother had done in Manzanar. Women also sewed thousand-stitch belts to keep these young soldiers, like Susumu Ito, safe on the battlefield.

Japanese immigrant parents took special language classes so they could write letters in English to their children as George Hara’s parents did. Some had to attend the funerals of their sons killed in action.

Risaku Kanaya is presented the Silver Star Medal posthumously awarded to her son, Pvt. Walter E. Kanaya.

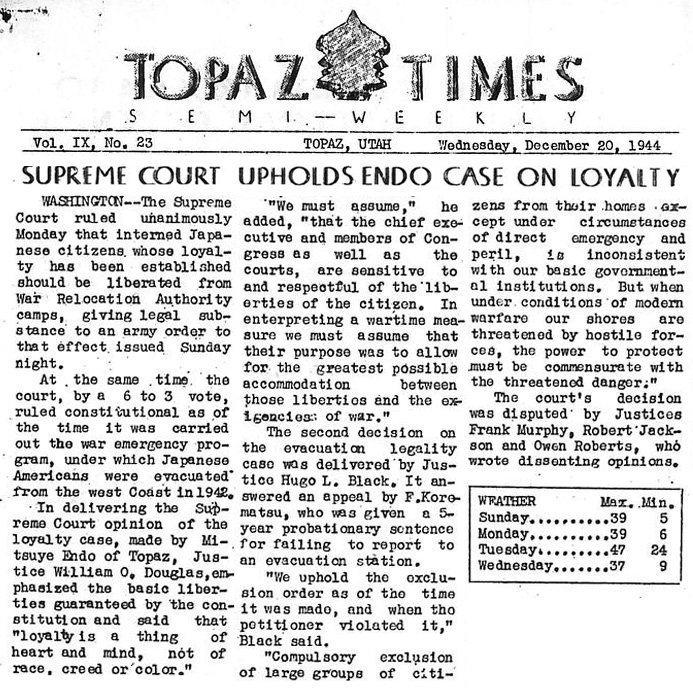

Supreme Court Ruling

On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court ruled on another case challenging the incarceration. This time, the plantiff, Mitsuye Endo, a Nisei woman, won the right to return to the West Coast. A day before the ruling, the Roosevelt administration rescinded the exclusion orders.

All Japanese Americans in every camp except for those segregated in Tule Lake could apply to return home in January 1945.

We are of the view that Mitsuye Endo should be given her liberty. |Justice William O. Douglas| in his opinion|

In the 1980s, declassified documents revealed that the US government knew that the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans was not a military necessity. This evidence was suppressed in the Supreme Court cases in the 1940s.

As a result, the court cases of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui were reconsidered. The respective federal convictions of all three were vacated and overturned.

Minoru Yasui's coram nobis legal team

The Supreme Court, however, has never ruled that the mass incarceration of people based on their ethnicity is unconstitutional. As a result, what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II could legally happen again.

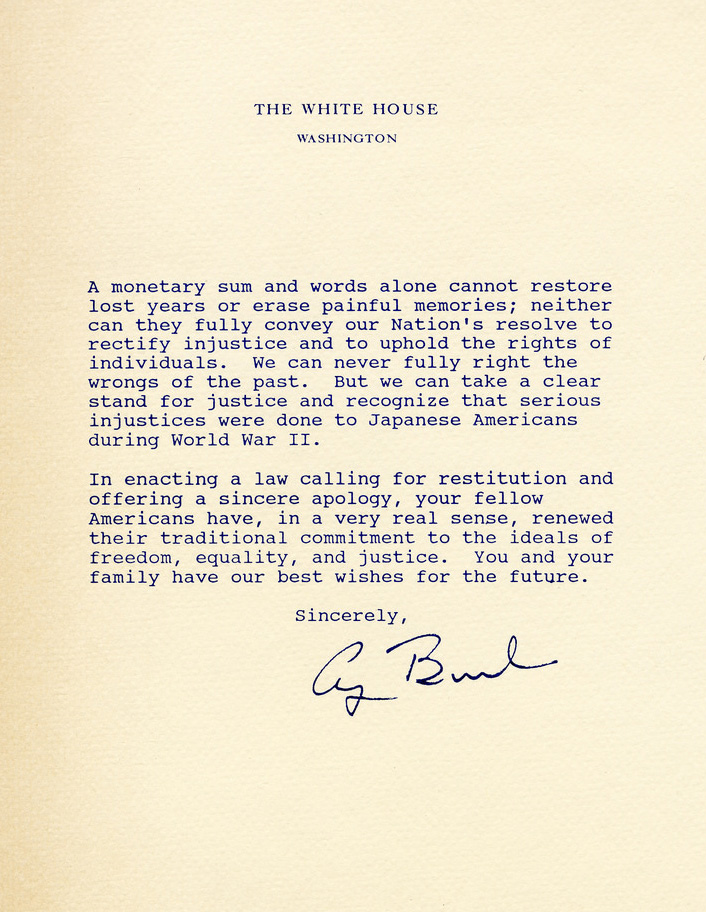

Yet through citizen action, Congress and the president offered an apology and compensation through the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Apology letter from President George H.W. Bush, 1990

Resources

To learn more about life in American concentration camps, visit Resources.

Credits

Photographs courtesy of Densho, Peggy Nagae, Holly Yasui, and the Smithsonian's National Musem of American History. The videos were made possible by AARP and A Tradition of Honor, Go for Broke National Education Center.