Technician Third Grade

Takejiro Higa

314th Headquarters

Military Intelligence Service

1923 -

- Citizenship

- Compassion

- Patriotism

Early Life in Hawaii and Japan

Born in Hawaii, a US territory, Takejiro had a difficult childhood. At age two he was taken to Okinawa, Japan, to visit his grandparents. Because of his young age, he stayed behind in Okinawa with his sick mother while his older siblings returned to the US with their father.

Within two years, both his parents and grandparents had died. He stayed with his uncle in Okinawa until he was 16.

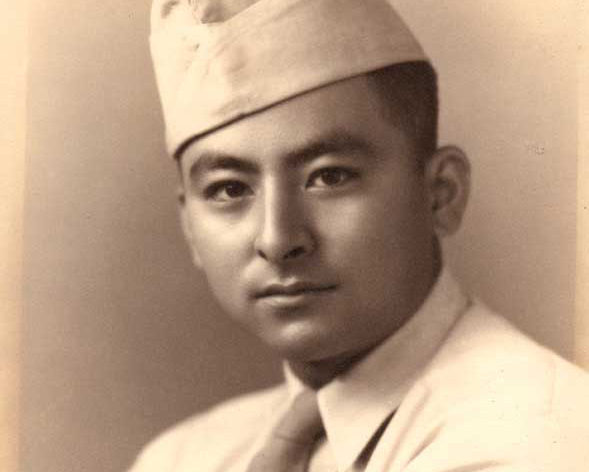

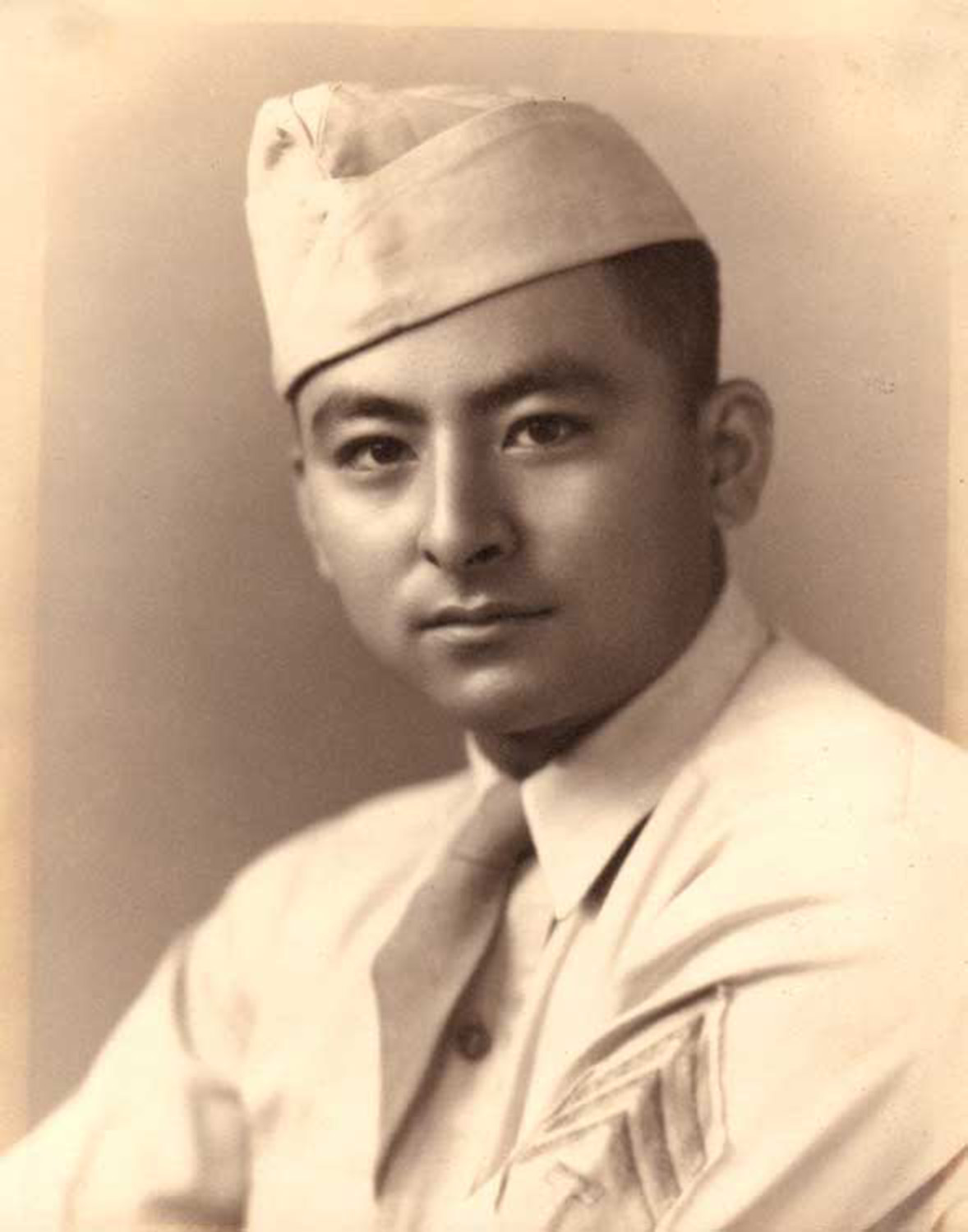

Takejiro with his mother and cousins

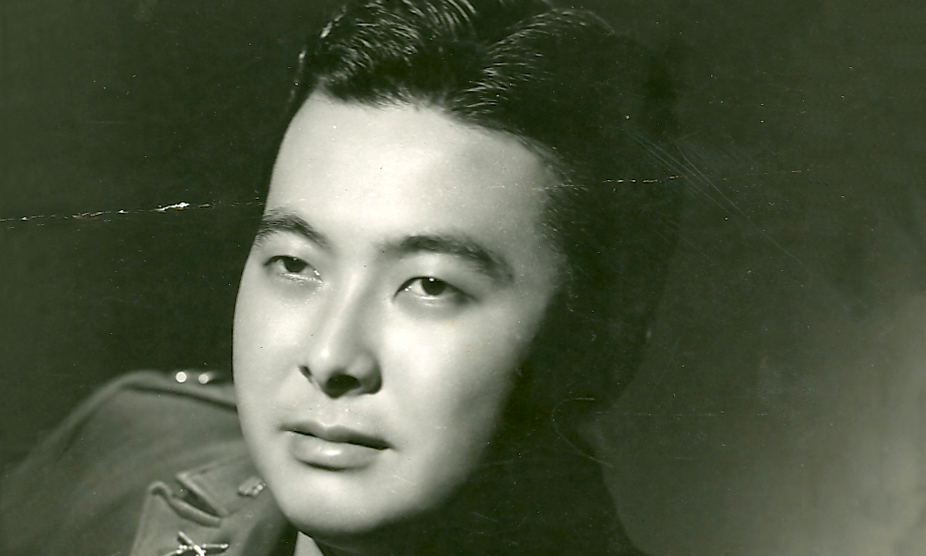

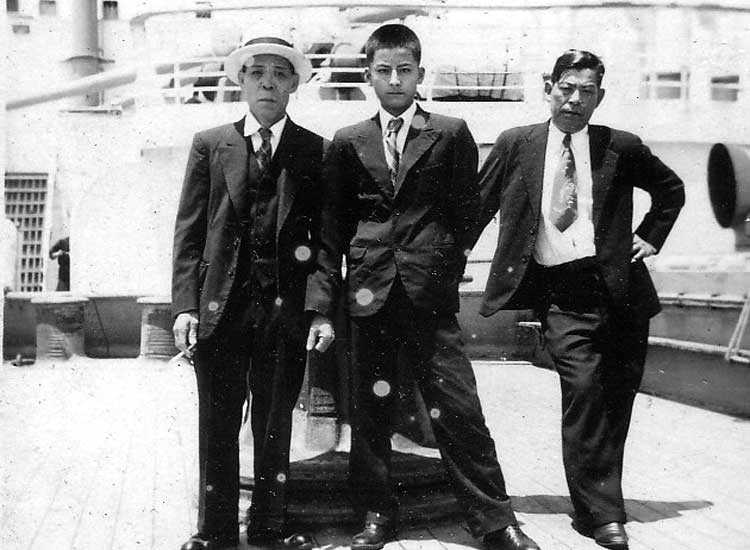

Takejiro Higa on the RMS Empress of Japan, returning to Hawaii from Okinawa

Seeking to avoid military conscription in Japan, Takejiro reunited with his older brother and sisters in Hawaii.

He could speak Japanese and Okinawan, but could not speak English well.

On December 7, 1941, Takejiro was working at the local YMCA, less than ten miles from Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. He heard that something was happening at the harbor.

He ran to the roof to see, not realizing that he would witness bombings by Japanese military planes and the entry of the US into World War II.

Bombing of Pearl Harbor

Farewell ceremony for Hawaii enlistees, 1943, Iolani Palace.

Japanese Americans were first classified as enemy aliens, 4C, by the US War Department. Once that classification was lifted, Nisei in Hawaii answered the US Army’s call for soldiers in overwhelming numbers.

Takejiro volunteered, expecting to fight in Europe. Since only a certain number of soldiers were needed, Takejiro was at first denied. His older brother, Warren, was accepted.

Takejiro was later recruited for a secret unit that would use the Japanese language to break codes and collect military intelligence in the Pacific.

What would he do if he encountered relatives or friends he knew across enemy lines?

Yet he had volunteered earlier, so he had to keep his word. Takejiro joined the Military Intelligence Service.

Takejiro’s brother, Warren, questions a prisoner about Japanese positions, Philippines, 1945

The Philippines and Okinawa

Takejiro and his brother became part of the division in charge of interrogating the enemy. Japanese soldiers were expected to die rather than allow themselves to be captured by the enemy.

With no interrogation training, those who were captured shared many secrets. Their confiscated diaries also gave the US important strategic information.

When in the Philippines, Takejiro was shocked to learn that their next target was southern Okinawa, his former home.

He was shown an image of Naha, the capital city, bombed beyond recognition. Seaside structures were thought to be military fortifications, but Takejiro explained that they were family tombs. With this kind of firsthand knowledge, Takejiro was recruited to help the US Army prepare to strike Okinawa.

I dreamed about my uncle, my cousins, and even my schoolmates.|Takejiro Higa| after learning that Okinawa would be the US Army's next target

Destroyed Okinawan Tomb

Conditions were difficult and casualties in Okinawa were heavy

The Battle of Okinawa was one of the bloodiest conflicts of the Pacific War. Nearly 240,000 American, Japanese, and Okinawan lives were lost.

Instead of laughter from his childhood, Takejiro heard gunfire and charges of “banzai.” He had to be accompanied by a non-Japanese American captain so his fellow soldiers would not mistake him for the enemy.

Takejiro’s knowledge of Okinawa and its language aided his interrogations.

He even encountered his former Japanese classmates, who did not know who he was at first.

[I said] 'Don’t you recognize your own classmate?' They looked at me in shock. |Takejiro Higa

MIS linguist interrogation of Japanese POW

Three of us grabbed each other's shoulders and I don’t mind telling you—we had a cry. |Takejiro Higa

Both Japanese soldiers and innocent Okinawan civilians, frightened about what Americans would do to them, hid in the islands’ numerous caves.

As the Allied Forces were close to victory, Takejro had to engage in cave flushing. Using the Okinawa dialect, he coaxed civilians safely out of the caves.

In another incident, a fellow Nisei linguist, Herbert Yanamura, spent three hours calling out to hidden villagers with a loudspeaker to peaceably surrender. About 1,500 finally came forward, saving their lives.

Post-War

Because the unit’s mission was classified until the 1970s, Takejiro could not publicly share his experiences for decades.

The Military Intelligence Service’s accomplishments were not a secret to leaders.

6,000 Nisei in the War in the Pacific saved over a million American lives and shortened the war by two years.|Major General Charles A. Willoughby|the Chief of Intelligence under General Douglas MacArthur

96th Infantry Division’s G-2, intelligence section. Takejiro Higa, Warren Higa, and Herbert Yanamura pictured

More than 70 years later, the prefecture of Okinawa recognized the invaluable contributions of Military Intelligence Service during World War II. Some of the civilians, children at the time, remembered the Nisei soldiers leading them to safety.

Takejiro and his comrades relied on their language skills to save the lives of civilians caught in the crossfire of war. Through their military service, they were able to secure peace throughout the Asia Pacific region.

Resources

To learn more about Takejiro Higa, visit Resources.

Credits

Photographs courtesy of Takejiro Higa, Densho, the Hawaii State Archive, the National Japanese American Historical Society, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, and the US Army Center of Military History. The video interview was made possible by A Tradition of Honor, Go for Broke National Education Center.