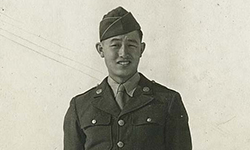

Technician Third Grade

George Hara

Military Intelligence Service

1925 - 2013

- Citizenship

- Compassion

- Perseverance

Early Life and Education

George always met his life challenges with a positive attitude.

He was a high achiever and became the class valedictorian in high school. Before he could graduate he was sent to the Portland Assembly Center. The seniors had an unofficial graduation ceremony behind barbed wire.

From Portland, George and his family were moved to Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho.

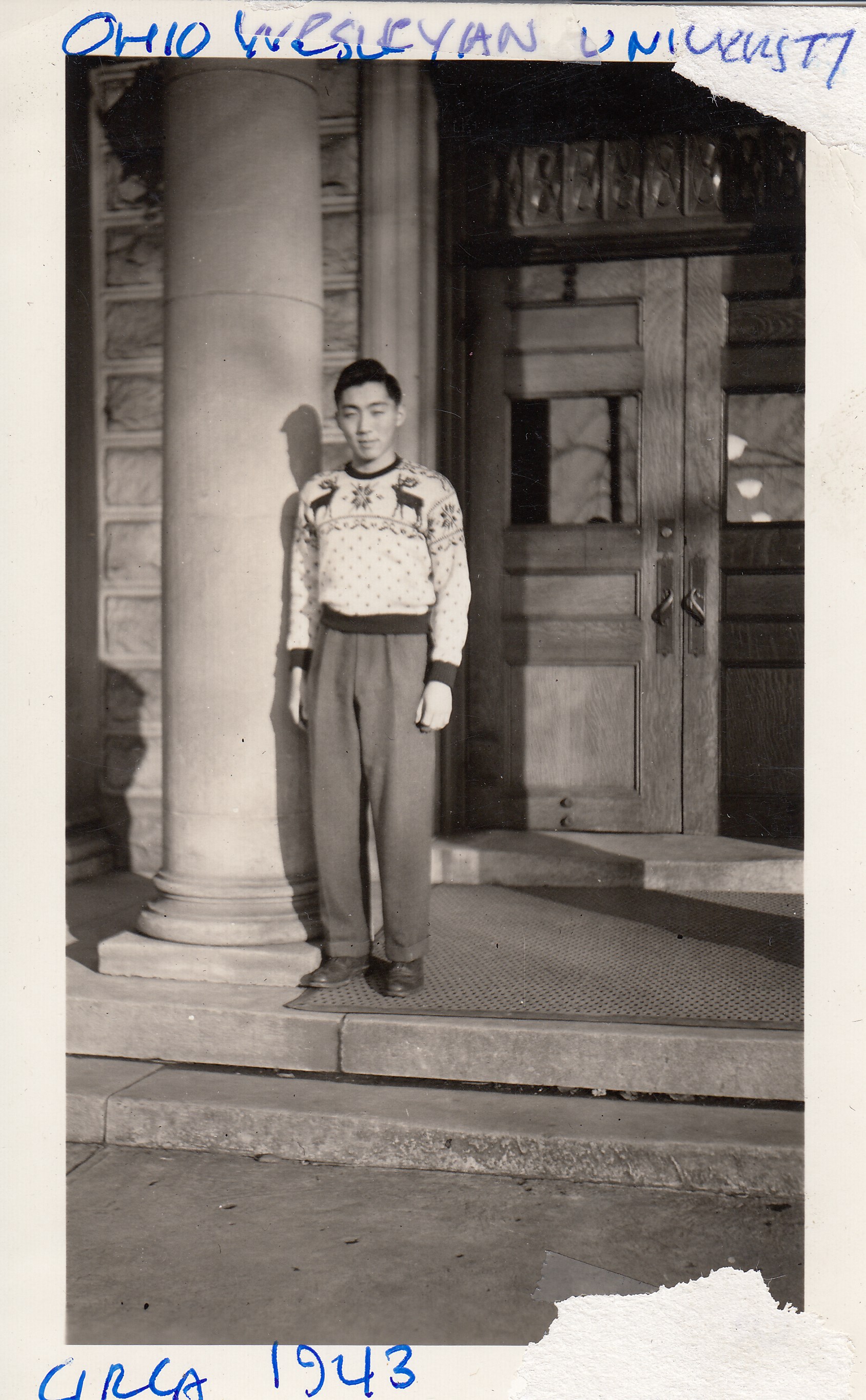

In 1943, he was able to leave camp to attend college, as long as the campus was located away from the West Coast.

George was a pre-med major at Ohio Wesleyan University.

His classes, friends, and Christian faith were favorite topics in his diaries during his time in Ohio. He also wrote of his excitement about enlisting in the US Navy, but he was eventually rejected because he was Japanese American.

I know a few V12 sailors and personally I’m very ‘green with envy’ as I couldn’t be one. I’ll try some more tho [sic].|George Hara’s diary entry|August 30, 1943

Anticipating being drafted in 1944, George rejoined his family in Minidoka.

He finally received his induction papers in camp and reported for duty in Minnesota.

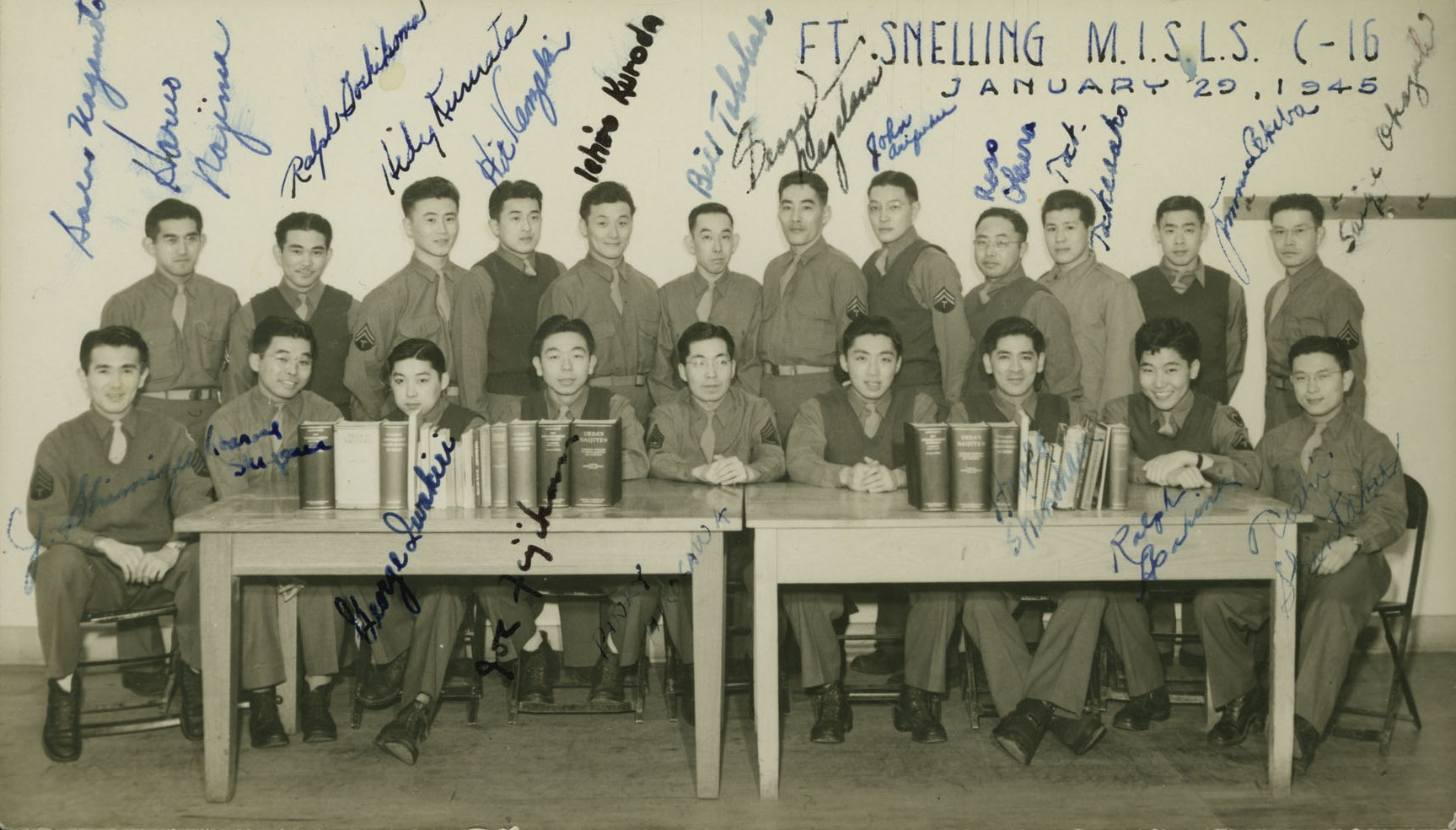

George and his classmates at the MIS Language School, 1945

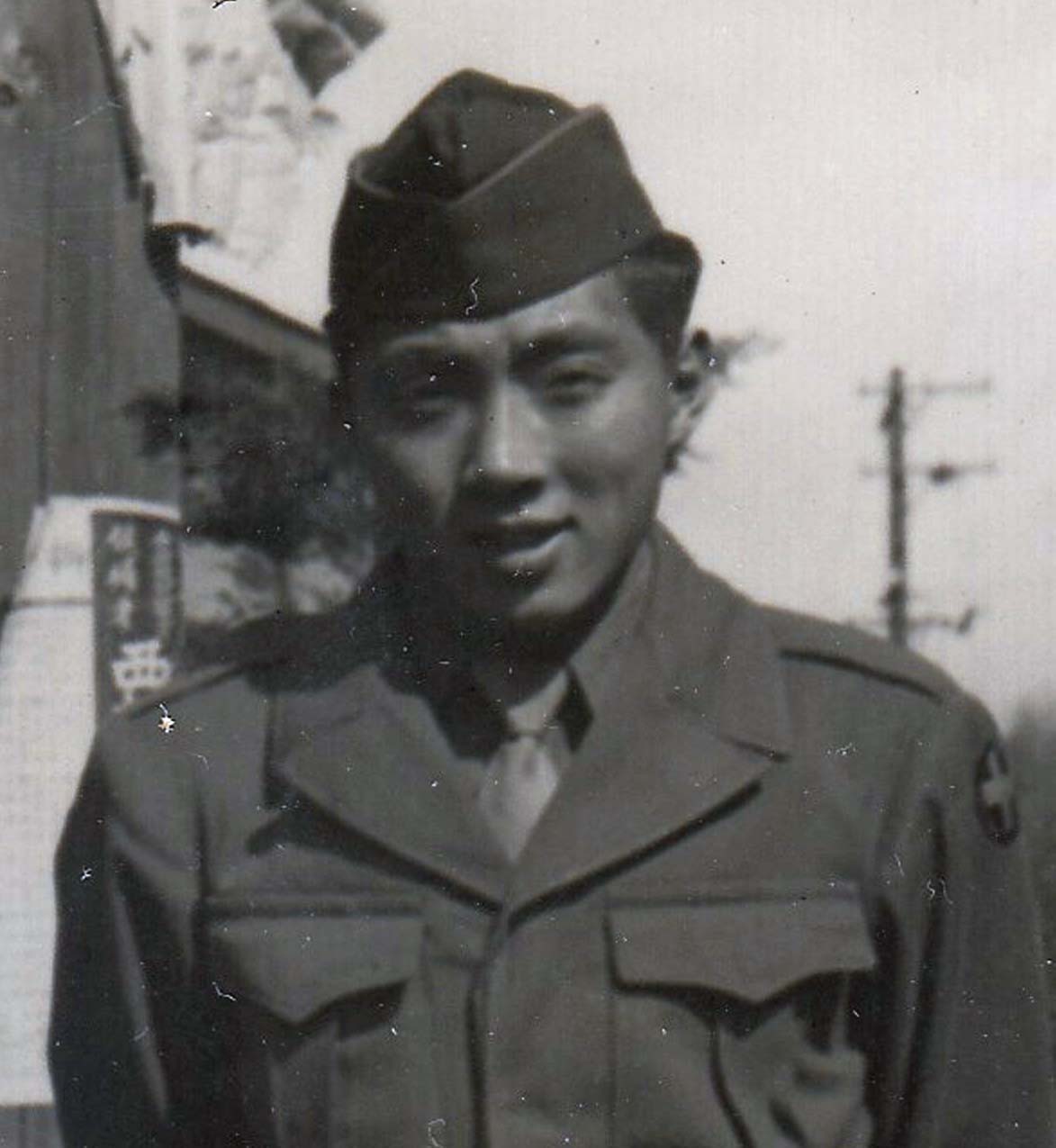

George was assigned to the Military Intelligence Service. Soldiers in this unit were sent to a special language school at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, to learn Japanese military terms, codes, and tactics.

In-depth knowledge of the Japanese language would be these soldiers’ secret weapon in defeating the enemy.

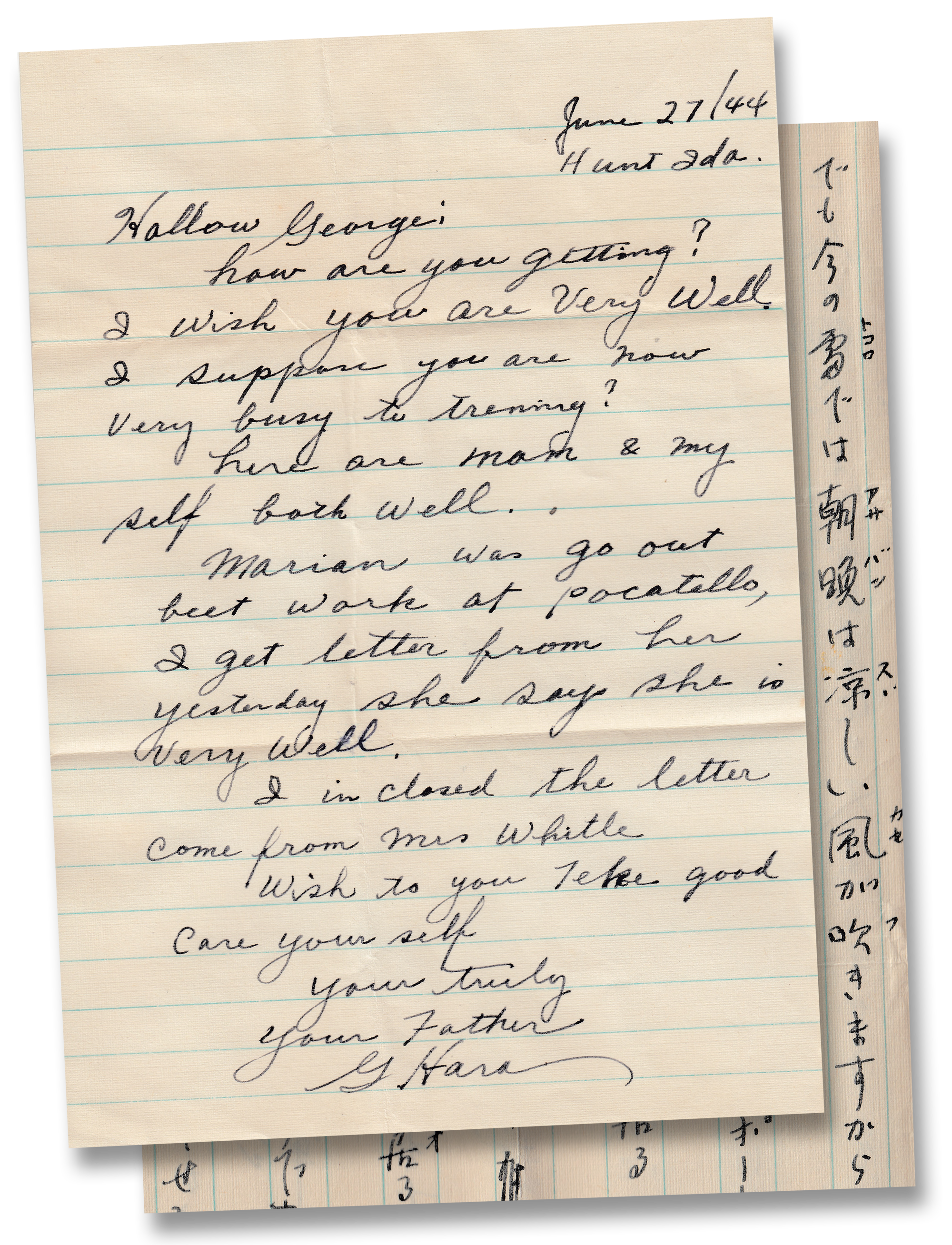

George’s immigrant parents wrote letters to encourage him in language school and provide updates on the family. While his mother wrote in her native Japanese, his father was studying English in the camp and carefully translated his letters to communicate with his soldier son.

I wish you are very well. I suppose you are now very busy to training.|Ginosuke Hara’s letter to his son George|June 27, 1944

Be honest, straight and do your military duties. God is looking after you.|Suye Hara’s translated letter to George|January 25, year unknown

Military Intelligence in the Philippines

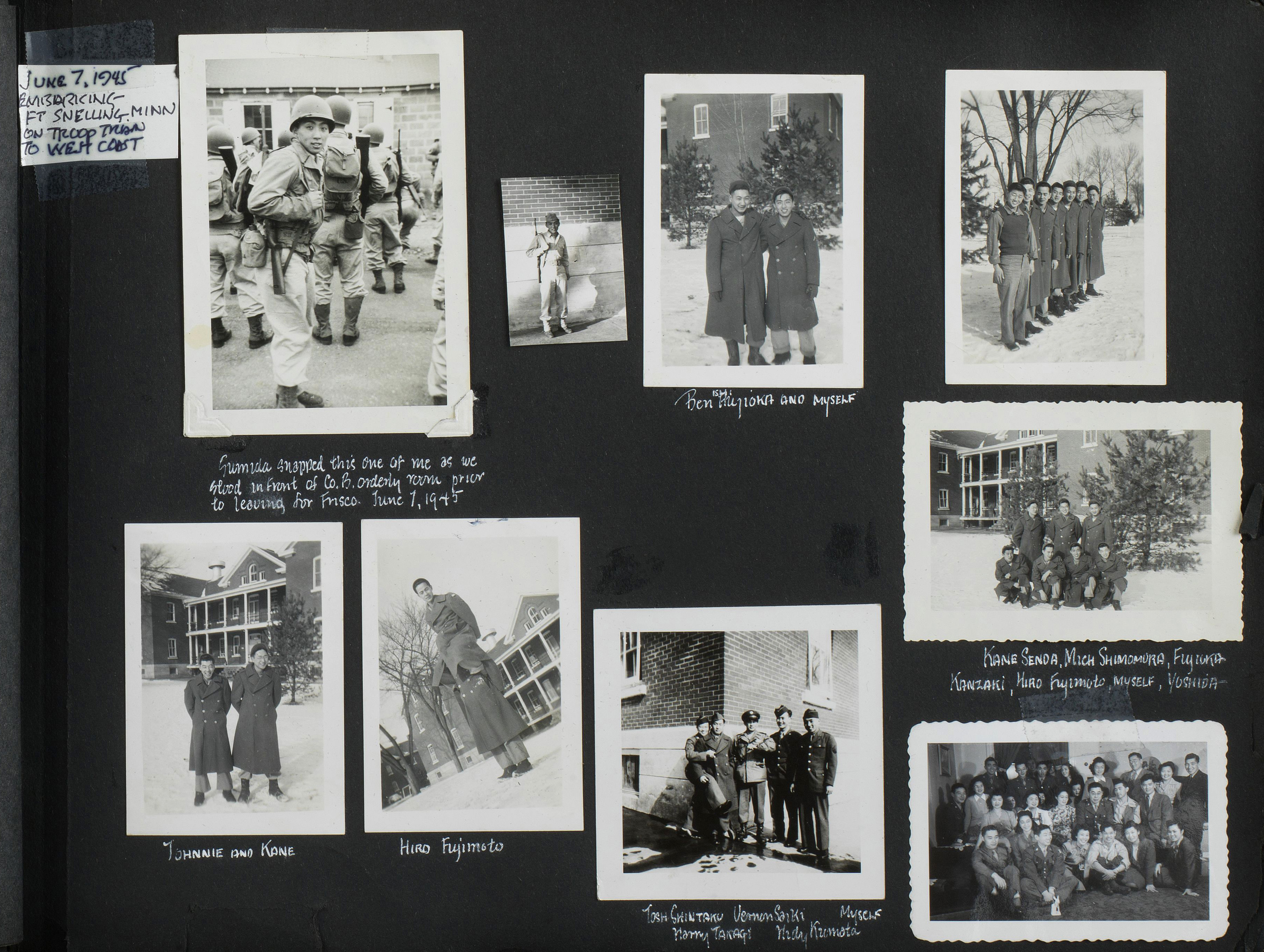

In summer of 1945 George left the US with other Nisei soldiers on a transport ship for the Philippines, which had been invaded by Japan during World War II.

George’s unit was eventually attached to the 33rd Infantry Division. Military linguists like George interrogated prisoners, translated captured documents, and used loudspeakers and leaflets to encourage surrender. Their translation work revealed the enemy’s plans, positions, and military operations.

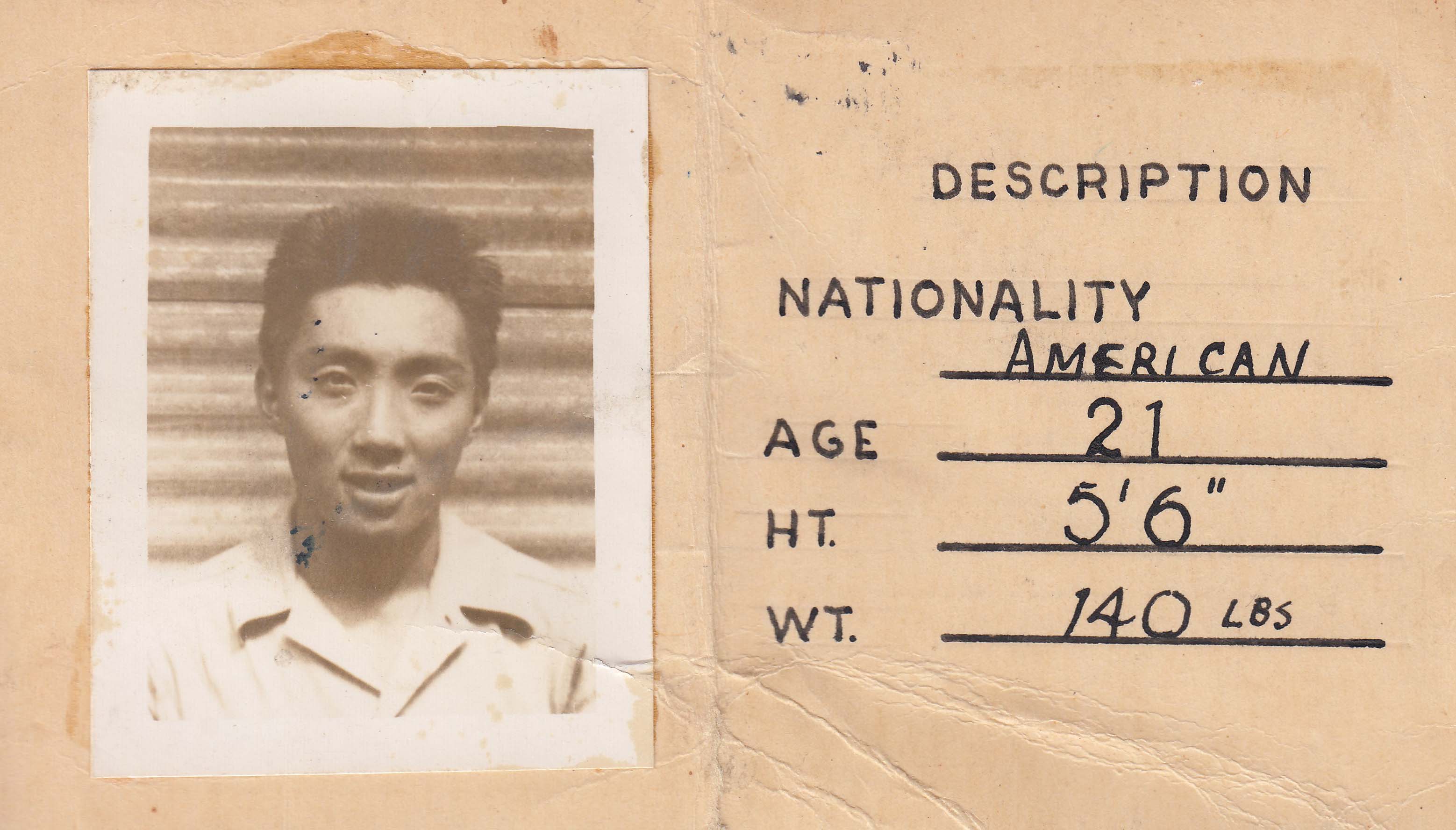

George identified as an American, rather than a Japanese American.

The casualties were tremendous in the Philippines. When the capital city of Manila was liberated from Japanese forces in March 1942, 100,000 civilians had been killed.

Nisei linguists like George knew that they would experience racial fallout from such losses. They explained to the people of the Philippines that they were Americans fighting for the US.

Occupation of Japan

Japan officially surrendered on September 2, 1945.

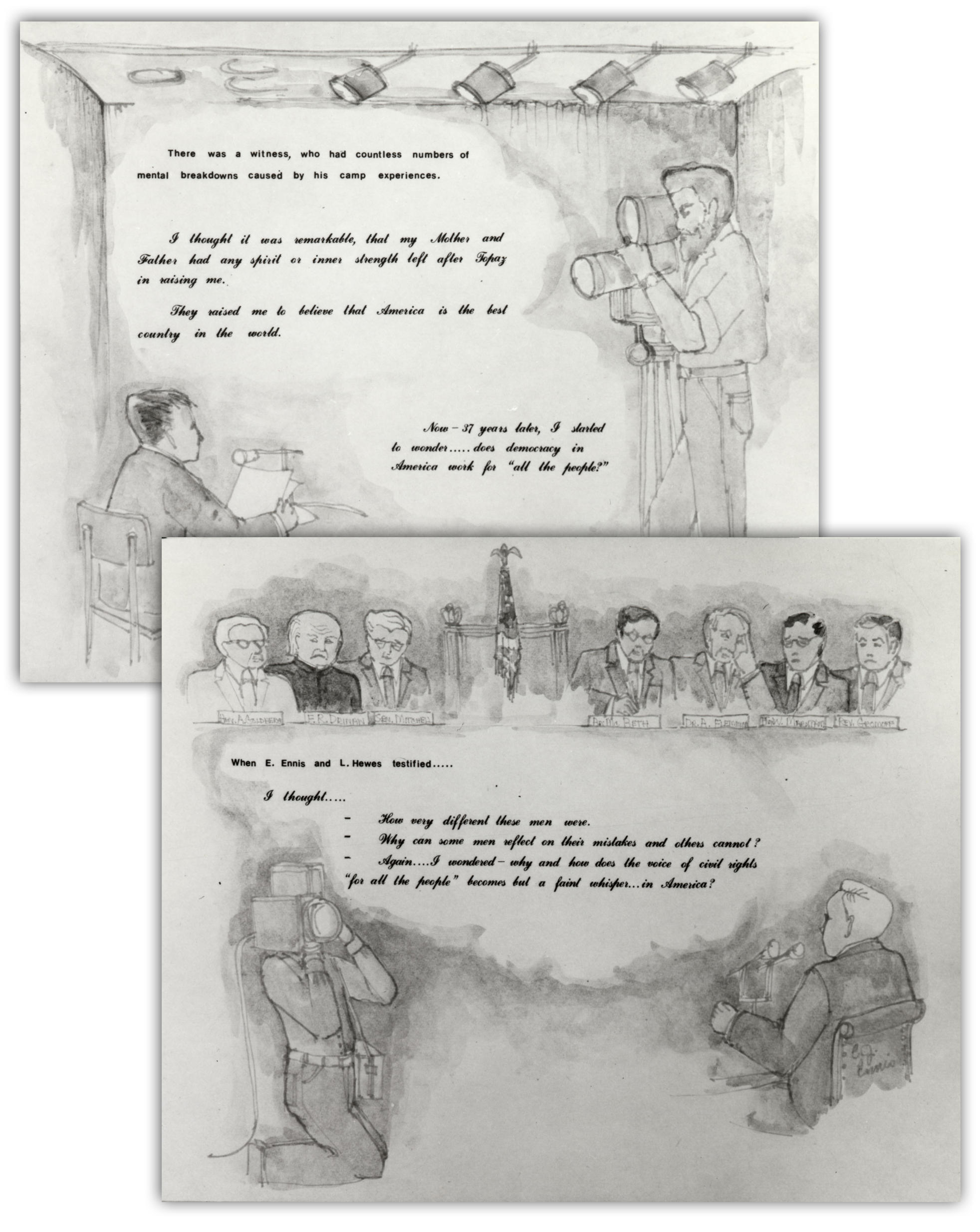

George then was sent to serve in the occupation of Japan. A gifted artist and writer, George kept a scrapbook throughout his service to record his experiences.

George and his fellow MIS language school attendees in Fort Snelling, Minnesota.

One of George’s most sobering experiences was when he visited Hiroshima, the site of the first atomic bombing.

Truly there is nothing as terrible yet invented by man, but how often has this been said before and history has been repeating itself time and time again.|from George Hara’s scrapbook

George captured several harrowing images in Hiroshima

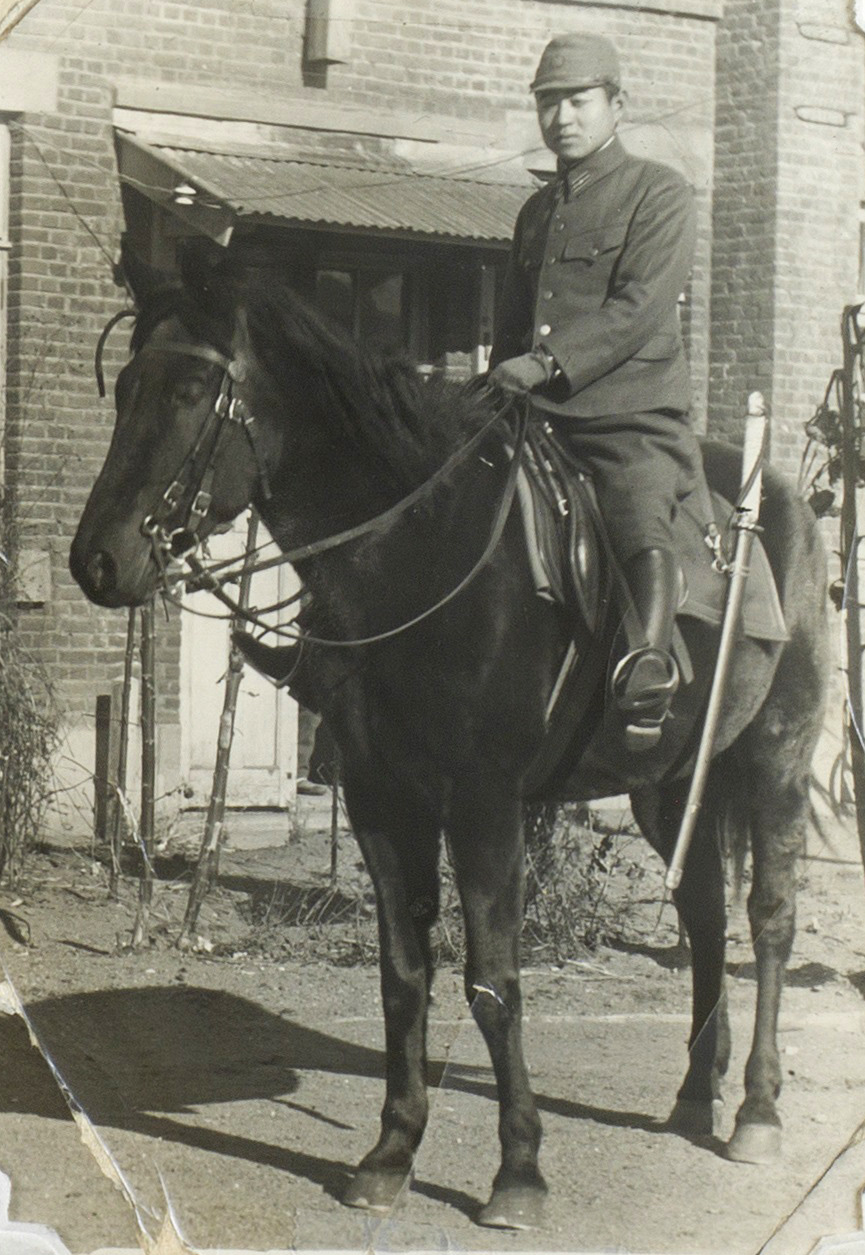

George’s cousin fought for Japan in Manchuria

George was also able to visit relatives in other parts of Japan.

He discovered that one of his cousins fought for Japan in Manchuria: two cousins on opposite sides of a war.

Post-War

After World War II, George was able to complete medical school and become a doctor, as he first intended.

He also became a member of the Japanese American Citizens League’s National Committee for Redress. Such groups helped to achieve redress and reparations in the 1980s for Japanese Americans incarcerated in the US World War II camps.

Of his many accomplishments, George was most proud of his tight-knit family. His wife Yoneko and his children remember him as a man who responded to wartime prejudice without “the weight of crippling bitterness.” Instead, he pushed through those boundaries with service to his family, community, and country.

Our father was a proud Nisei. ... For those of us who follow, the loads on our backs are lighter because he challenged discriminatory limits. His legacy is a grateful, nurturing family guided by his successes, compassion, generosity and love of life.|George Hara’s children

Resources

To learn more about George Hara, visit Resources.

Credits

Photographs and images courtesy of Yoneko Hara and family and the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. The video interview was made possible by the Oregon Nikkei Endowment.