From Exclusion to Representing America

The journey of Japanese Americans in the US has been marked with struggle. Between 1861 and 1940, some 275,000 Japanese came to Hawaii or the American mainland. Nearly all arrived after 1898 and before 1924, when legal restrictions ended Asian immigration. While their labor was desired, they were not welcomed into American society.

Japanese sugar plantation laborers at Kau, Hawaii Island

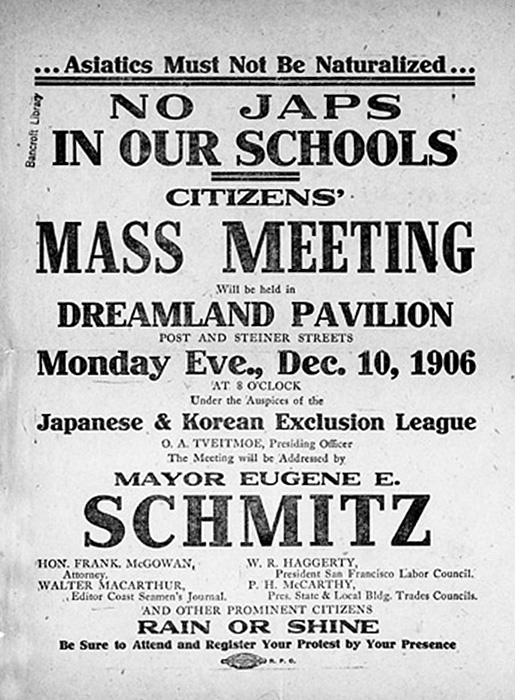

With the rise of anti-Japanese agitation, President Theodore Roosevelt was forced to take a strong stand to protect the Japanese in the US. Under the terms of what came to be called the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-08, Japan agreed to restrict the immigration of laborers to the US and the US agreed not to discriminate openly against the Japanese.

"No Japs in Our Schools / Citizens' Mass Meeting," 1906

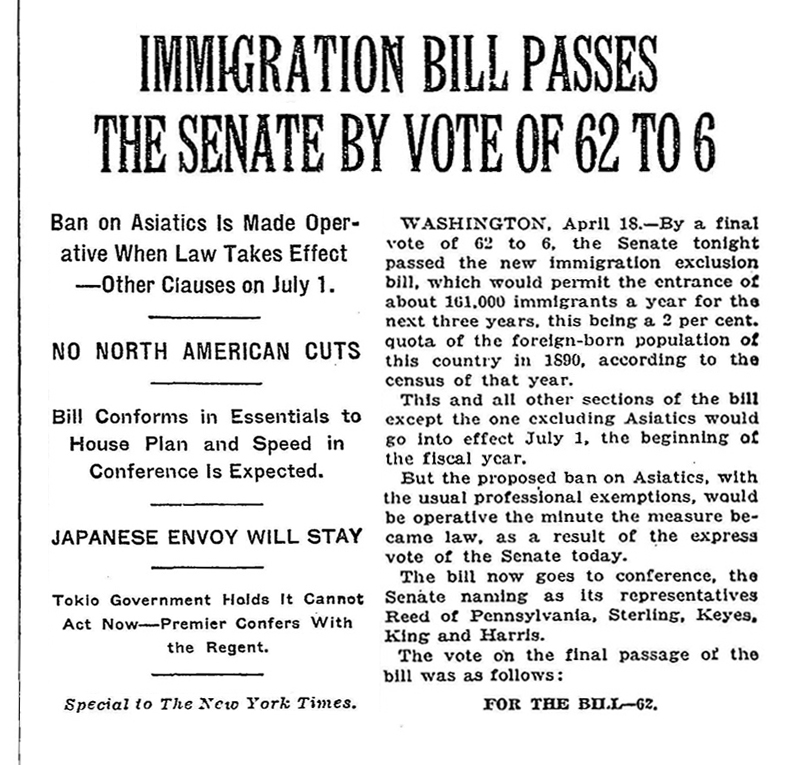

Passage of Immigration bill, the New York Times, June 12, 1952

Banning Entry of Japanese

Japanese immigrants could not buy or lease land for long periods of time. While European immigrants could become naturalized citizens, newcomers from Asia could not.

Finally, in 1924, an immigration act was passed that barred new Asian immigrants from coming into the US.

Anti-Japanese feeling grew in the West, particularly in

California. For example, California had

anti-miscegenation laws

that banned

marriages between whites and nonwhites, including blacks and Asians, until 1967

when the US Supreme Court officially put an end to any state’s ban on

interracial marriage.

The Japanese American community was under government surveillance even before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941.

After the US formally entered World War II, Japanese leaders of language schools, temples, and other organizations were immediately arrested by FBI agents. They were sent to Department of Justice internment camps in faraway places like Montana, North Dakota, and New Mexico. By February 1942, Executive Order 9066 forced the relocation of 110,000 Japanese Americans into 10 American concentration camps across the US.

No Japanese American in the US was ever convicted of espionage or sabotage.

FBI searches a Japanese American home.

"WRA DIRECTOR CASTIGATES FOUR GROUPS OPPOSING RETURN OF NISEI EVACUEES TO WEST COAST."

After Japanese Americans were released from American concentration camps in the 1940s, they had to completely rebuild their lives.

Restrictive covenants limited where blacks and “Mongolians,” or Asians, could live. These racial covenants were overturned by the Supreme Court in 1948, but Japanese Americans still found it difficult to settle in more white neighborhoods.

The Nisei still faced job discrimination. Many, even college-educated ones, had to do manual work during the resettlement period. In Hawaii, early opportunities were in teaching and small business. But the sacrifices and patriotism of Japanese Americans during a dark time of US civil rights history did not go unnoticed. In 1948, President Truman called for an end to segregated military units.

You fought the enemy abroad and prejudice at home and you won. |President Harry Truman|on July 15, 1946, regarding the 100th and 442nd Regimental Combat Team

Nisei leaders continued to advocate for their parents’ status in the US. In 1952, through a controversial legislative act, Japanese immigrants were finally allowed to become naturalized citizens.

Issei, many of whom had been incarcerated, answered the call of citizenship.

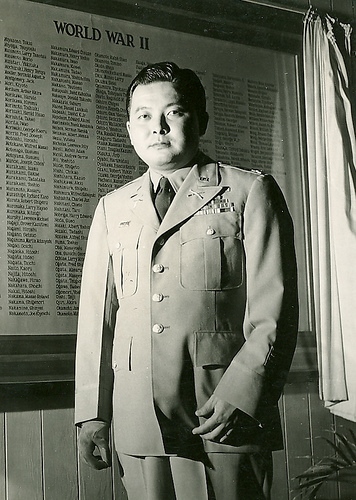

Dan Inouye served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated unit, in World War II.

Dan Inouye, a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was the first Japanese American to be elected to the US House of Representatives and Senate. Other Japanese Americans also became active in both electoral politics and civil rights community organizing.

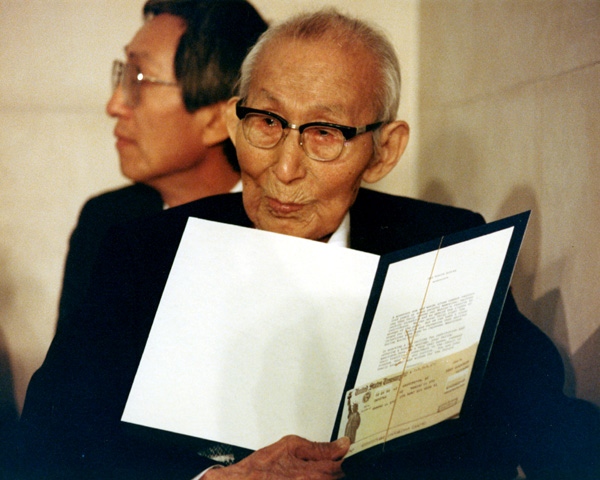

Redress and Reparations

Through the mobilization of various groups, Japanese Americans successfully fought for redress and reparations for those who had been incarcerated in America’s concentration camps.

The legislative bill—the Civil Liberties Act of 1988—included a presidential apology and compensation.

First reparations check is presented to 107-year-old Mamoru Eto at Great Hall, US Department of Justice, Washington, DC.

Contemporary Pioneers

Japanese Americans have also made their mark in other areas.

Figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi, whose mother was born in an American concentration camp, represented the US in the 1992 Winter Olympics. She won a gold medal.

George Takei, a former internee, was a member of the Starship Enterprise in the iconic “Star Trek” TV show. Now a social media sensation, he staged a Broadway musical inspired by his camp experiences.

George Takei and Kristi Yamaguchi

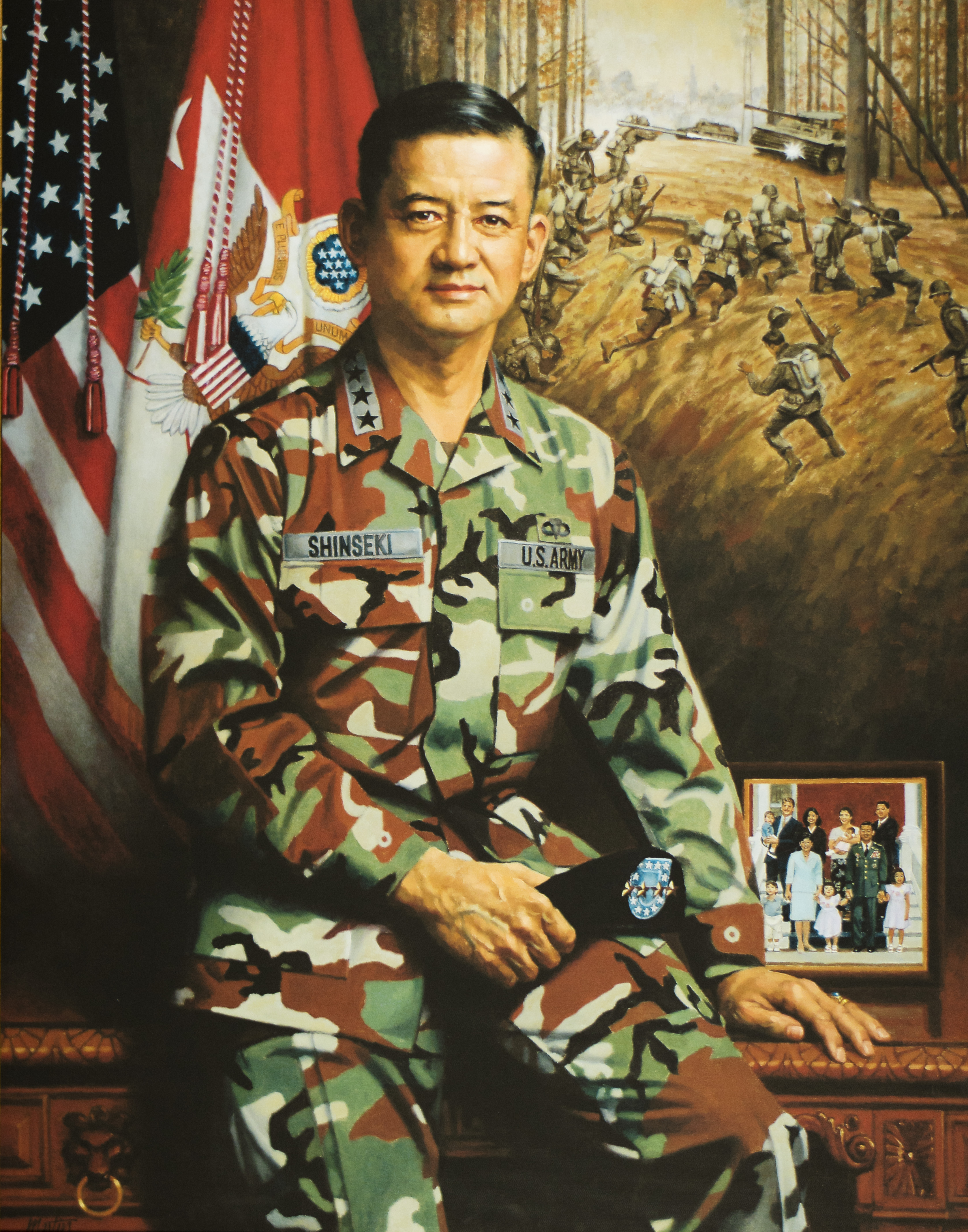

Inspired by three uncles who served with the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Hawaii-born Eric Shinseki pursued a career of military service. He became the first Asian American to become a four-star general and US Army Chief of Staff. He later served in the President's Cabinet as Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

Portrait of Eric K. Shinseki, US Army Chief of Staff, 2003

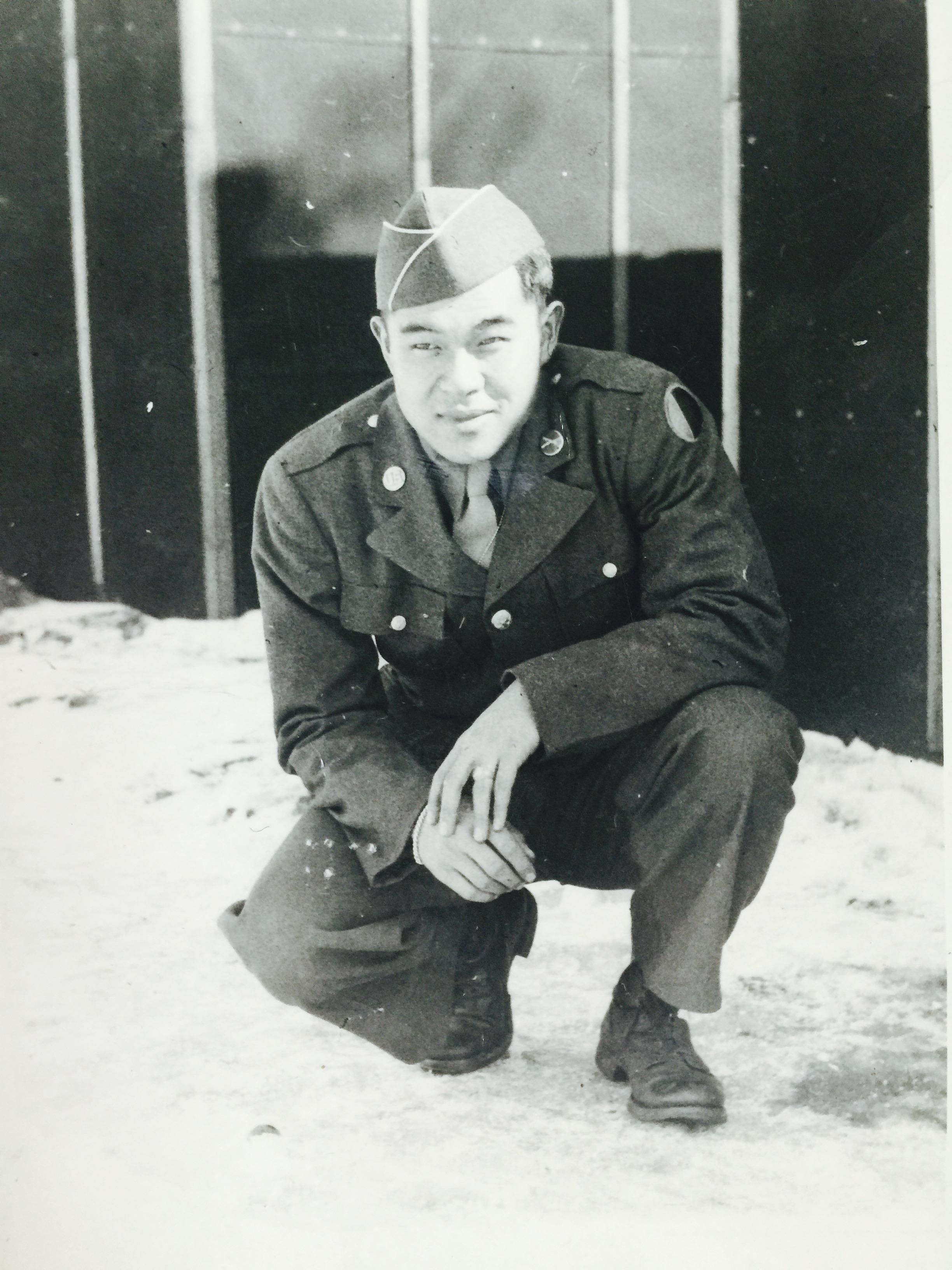

Albert Mineta at the MIS Language School Fort Snelling, Minnesota

Norman Mineta was 10 years old when he and his family were sent to an American concentration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

His older brother Albert signed up for the US Army in 1945 and was one of the first to arrive in the Occupation of Japan. He used his Japanese language skills to help secure peace and establish a democratic Japan.

After the war, Norman began his career in government.

Norman Mineta was a member of the presidential cabinet when the Twin Towers in New York City were destroyed in a terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. Norman had previously told President George W. Bush that as a young boy he had been incarcerated in Heart Mountain concentration camp.

When people are acting out of wartime hysteria, that’s the time to make sure that you don’t.|Norman Mineta|in speech at Hunter College, 2014

President Obama salutes Tommie Okabayashi, 442nd RCT soldier, from Houston, Texas, February 2015

Over the past 75 years, Japanese Americans have made significant strides. Yet the question of loyalty as it relates to race has resurfaced in this post-9/11 world.

We look back to events during World War II with hope that we as Americans have learned these lessons of history.

The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry.|President Franklin Delano Roosevelt|February 1, 1943

Resources

To learn more about post-war achievements, visit Resources.

Credits

Photographs courtesy of the 100th Infantry Battalion Education Center, the Daniel K. Inouye Institute, Densho, George Takei, the Hawaii State Archive, Norman Mineta, the Okabayashi family, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, the University of Wyoming, and the US Army Center of Military History. The video interview was made possible by the National Veterans Network.