Private

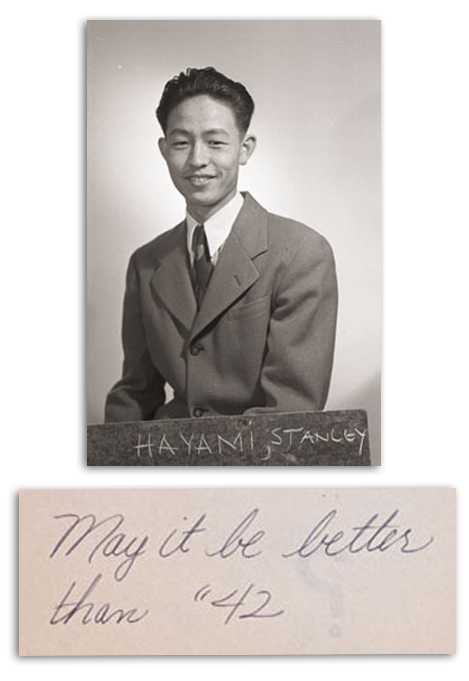

Stanley Hayami

Company E

442nd Regimental Combat Team

1925 - 1945

- Citizenship

- Compassion

- Patriotism

- Sacrifice

Early Life at Heart Mountain

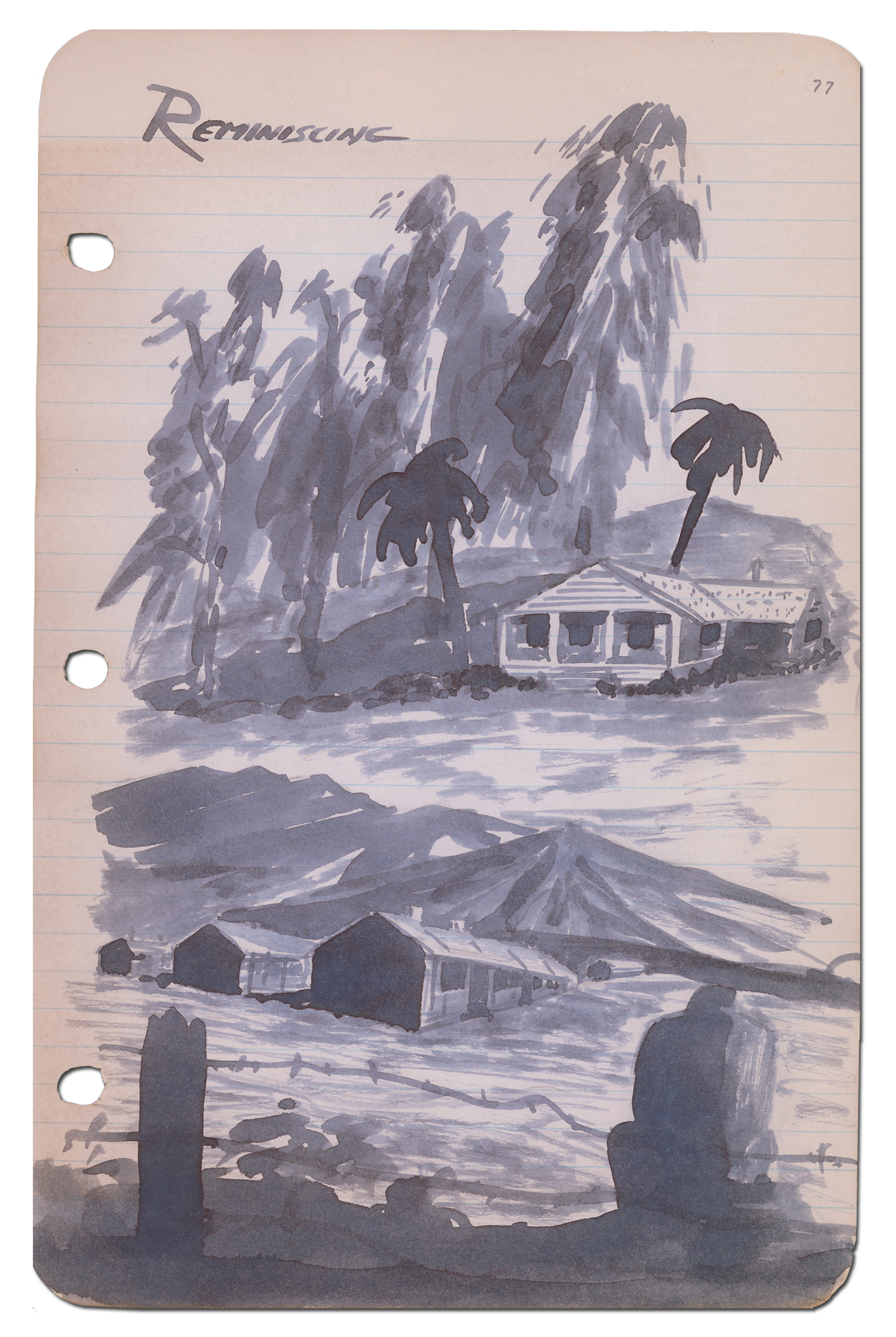

Stanley Hayami’s tremendous journey from being imprisoned in a Wyoming concentration camp to fighting abroad is preserved through his wonderful drawings, earnest journal entries, and heartfelt letters home.

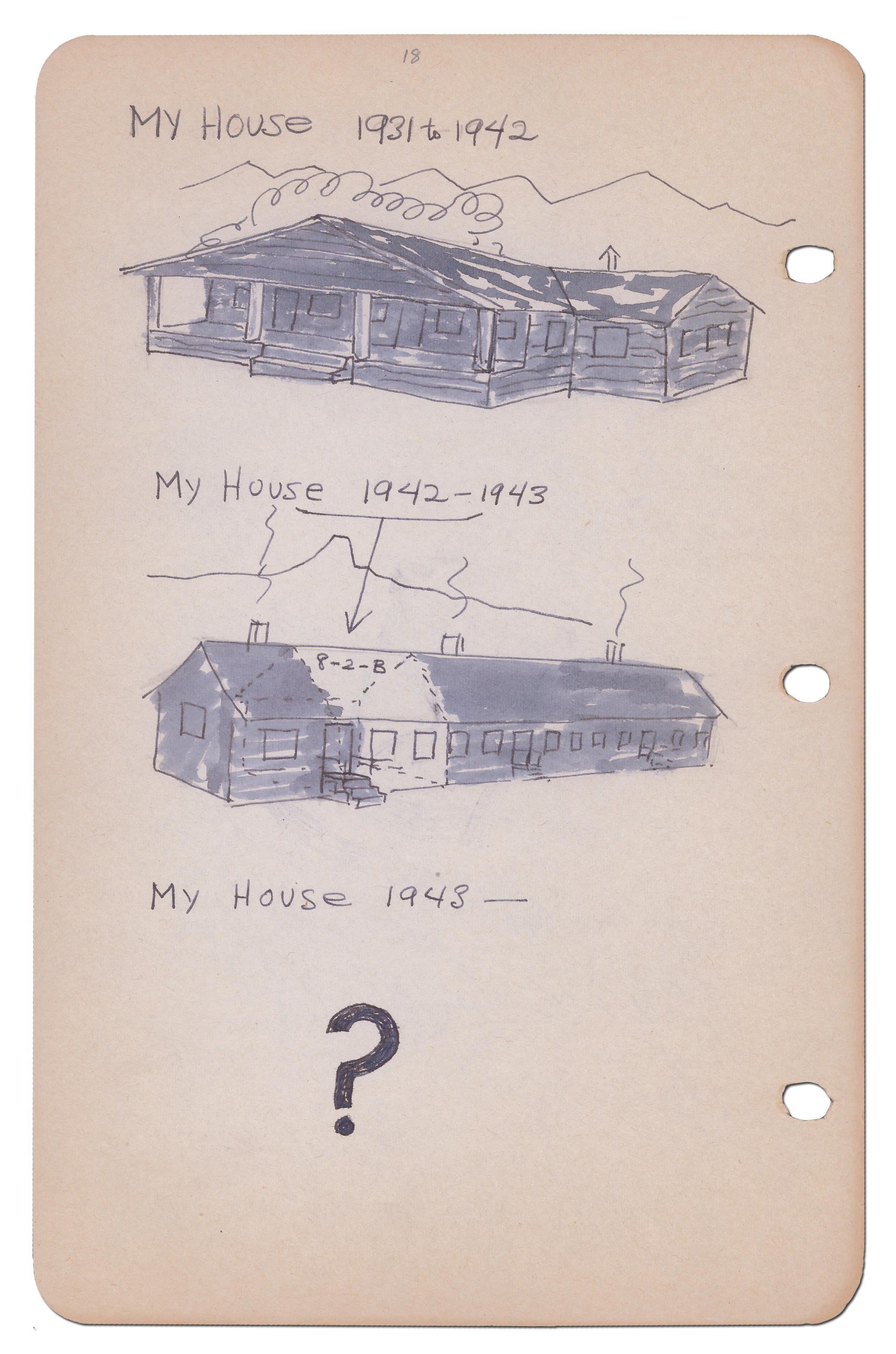

Home in San Gabriel vs. the camp at Heart Mountain

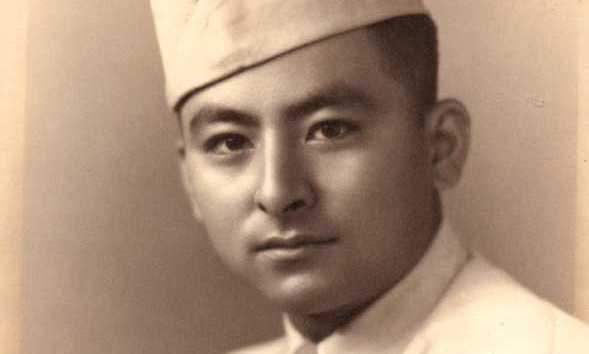

Left: Stanley Hayami, Right: Stanley and Walt Hayami eating in the mess hall, 1944.

Stanley was born in 1925 to Naoichi and Asano Hayami in San Gabriel, California.

When he was just 16 he and his family were uprooted from their home and sent to the camp at Heart Mountain.

His journal from this period captures the tender reminiscence of a boy coming of age in uncertain times.

"Well today is the first day of the year nineteen hundred and forty three. I wonder what it has in store for me? Wonder what it has in store for everybody? Wonder where I’ll be next year? Wonder when the war will end? Last year today, I said I hoped that war would end in a year. Well it didn't but this year I say again 'I hope the war ends this year, but definitely.' Another thing is, I hope I'm out of here and a free man by ‘44." |January 1, 1943

Home before, in the camp, and beyond…

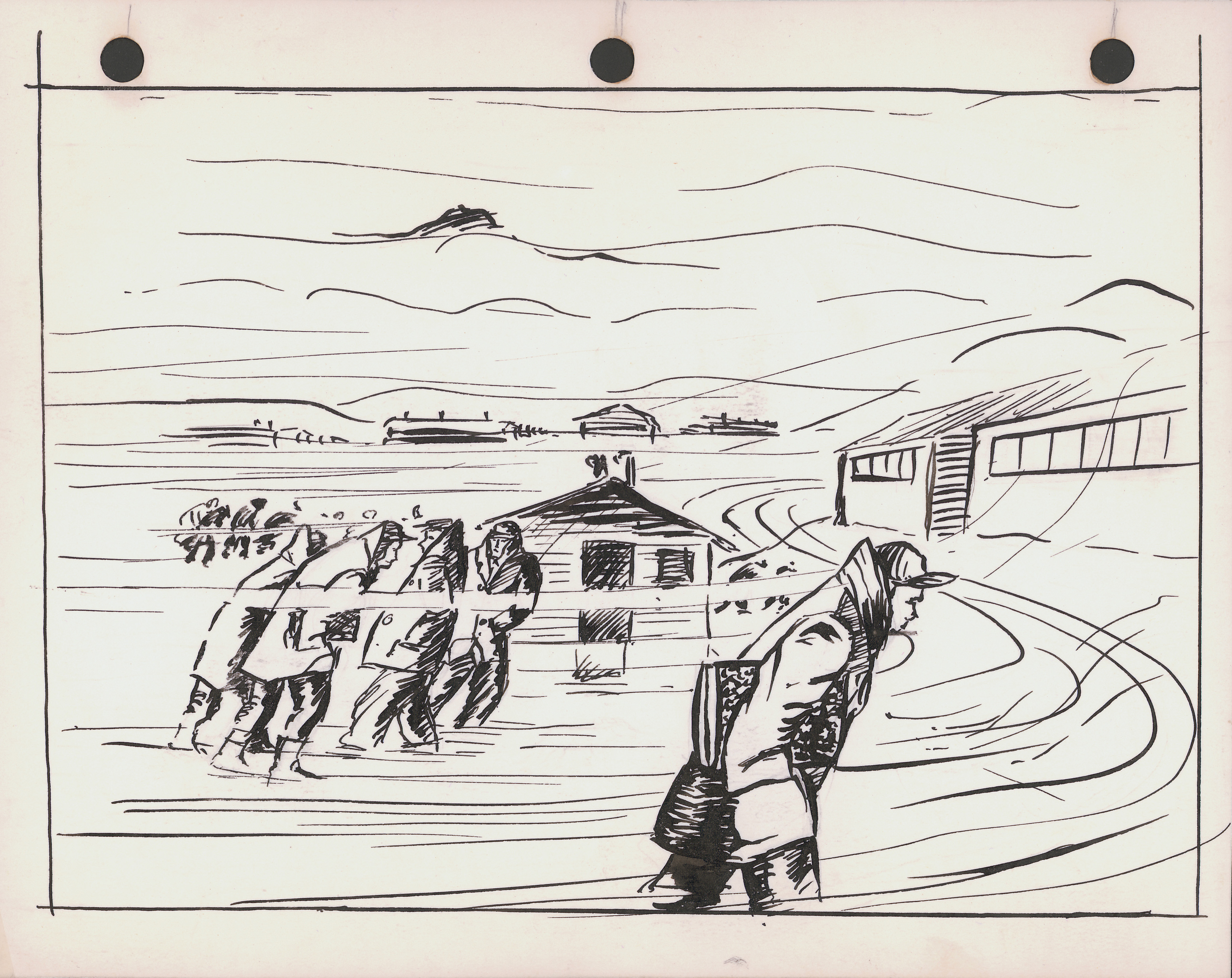

Cold Weather at Heart Mountain

Within these pages Stanley recounted the daily life of a teenager. Sometimes he touched on topics common to any American high schooler, such as sports, school, and fitness. At others he detailed the harsh conditions in the camp, exploring questions of loyalty to his country or other topics unique to his experience.

The announcer on the radio from L.A. (?) just said that he envied us back east, who will have a white X-mas. Heck I envy him more: Wish I were back home to see a nice Green X-mas not a white X-mas.

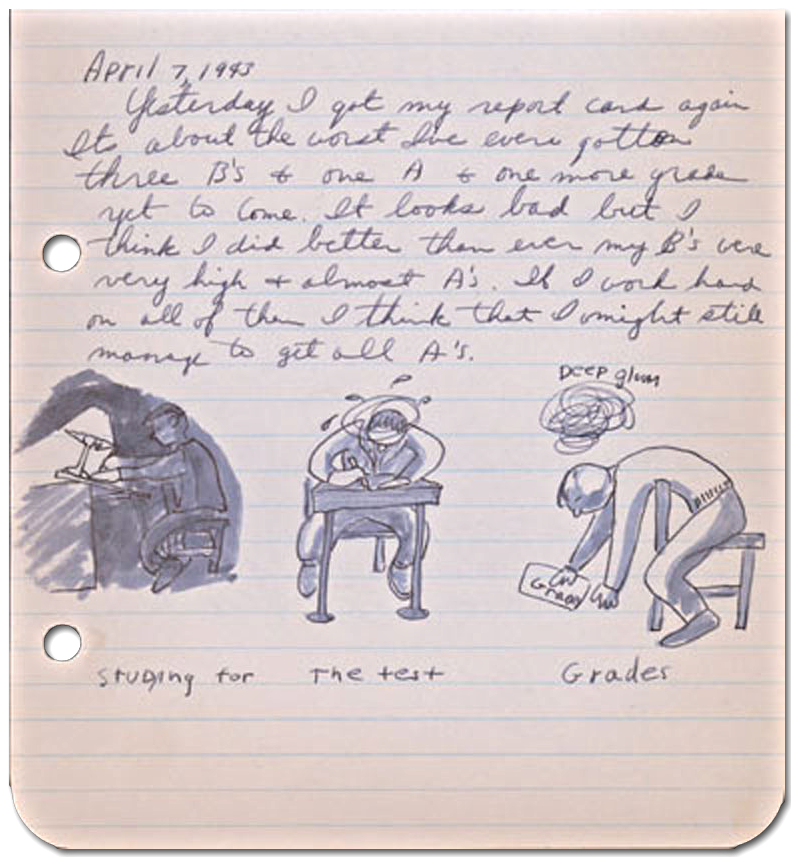

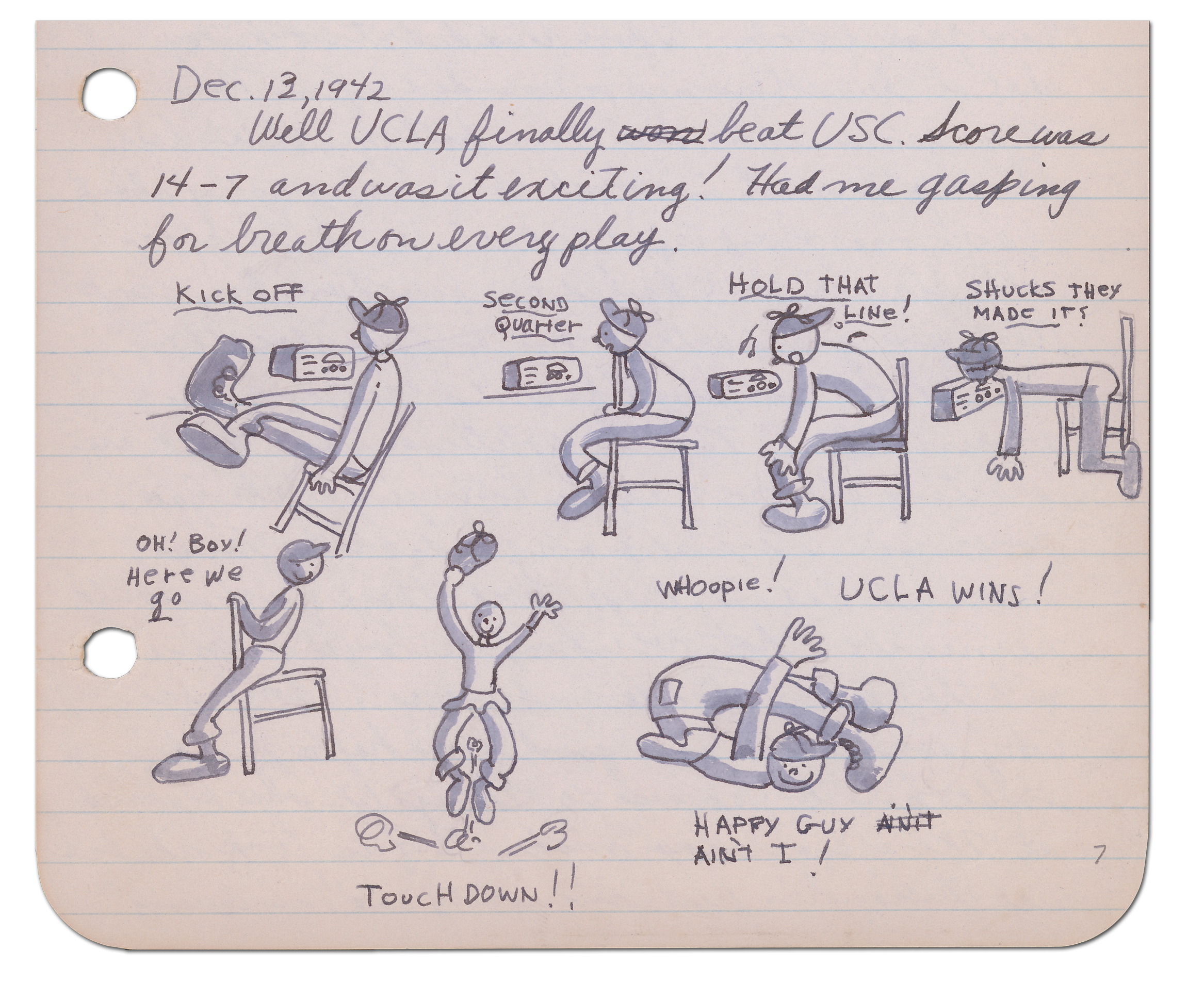

Familiar Struggles

Stanley wrote often of school, expressing concerns about his grades or how difficult his tests were, but overall he worked hard and was a strong student.

Stanley illustrates how happy he was when UCLA beat USC at football. (December 1943)

Stanley’s warm-hearted optimism comes across in his writing, peppered with terms such as “shucks” and “doggonit.” But his often playful illustrations truly capture his emotional landscape.

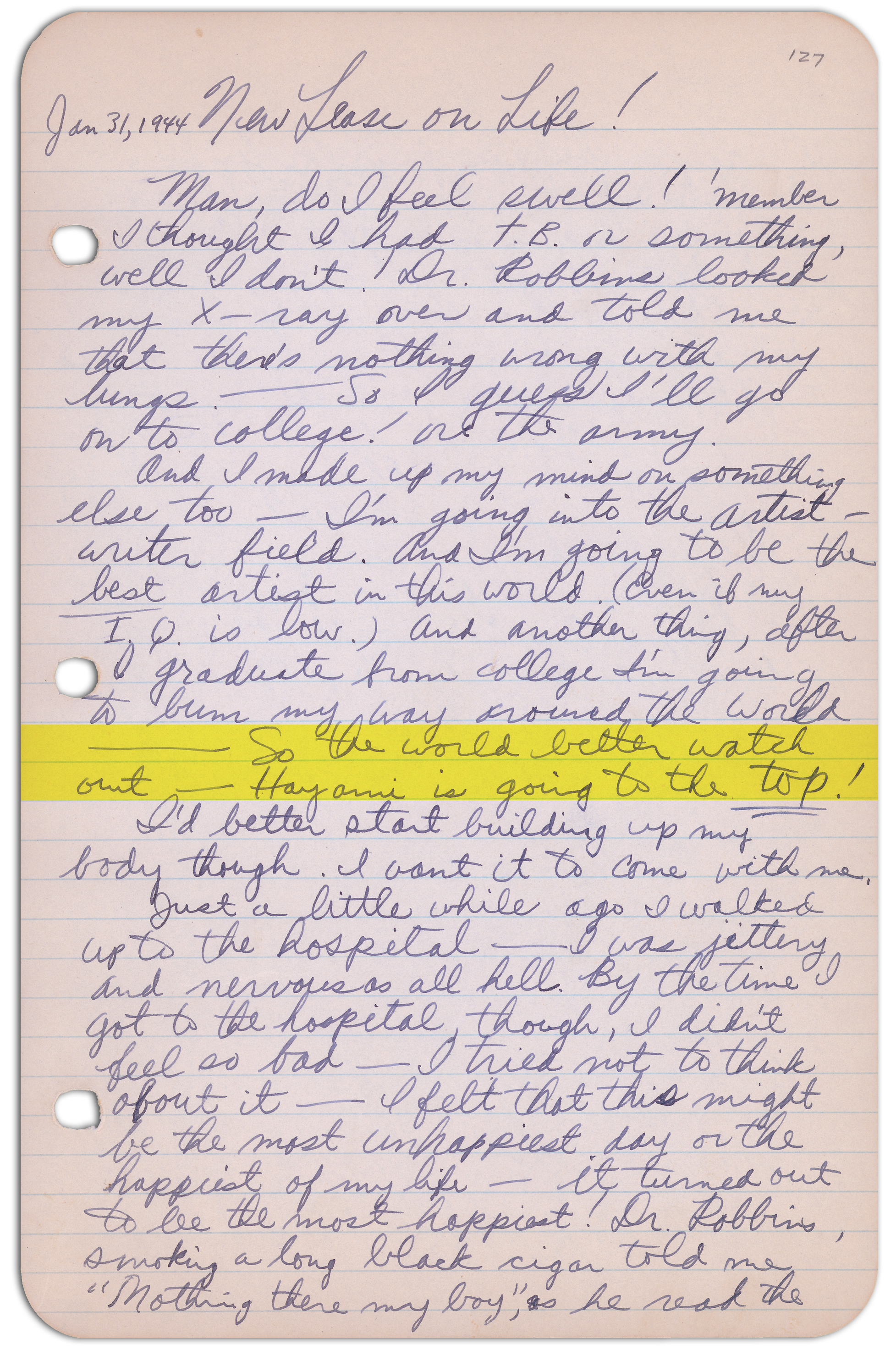

Like many teenage boys, Stanley was very slim for his height. Added to some other health complications, this made him mindful about his appearance and fitness.

Stanley explained his excitement that he didn’t actually have an illness as he thought previously. He was optimistic about the future and proclaimed

So the world better watch out—Hayami is going to the top

"Man, do I feel swell!"

Unique Challenges

Stanley’s thoughts on civil rights are as insightful as they are heartfelt, and quite sophisticated for a boy of his age. He writes of his incarceration as unconstitutional and involving racial bias. He weighs in on very difficult questions, such as whether or not the decision to intern Japanese Americans was worthwhile for the government.

In his final analysis he states:

I think that the whole mess was unnecessary and a lot of trouble could have been avoided. ... I personally will proceed to forget the whole mess, will try to become a greater man from having gone thru such experiences, keep my faith in America, and look forward to relocation and the future.

At the start of 1943, his last full year in the camp, Stanley outlines his New Year’s resolutions:

to be more tolerant … to be more understanding of others and more appreciative … to study as hard as I can and learn as much as I can.

Stanley and his family

More than 800 in the camp chose to enlist, although how this might impact Japanese Americans after the war was uncertain. Stanley captures this dilemma: "The army man … says that if we volunteer it’ll do a lot to show our loyalty, and improve the relations and opinions of the American people toward us. It’ll show that we are truly Americans, because we volunteered despite the kicking around that we got. On the other hand however he says if we all do not volunteer … it would make it worse."

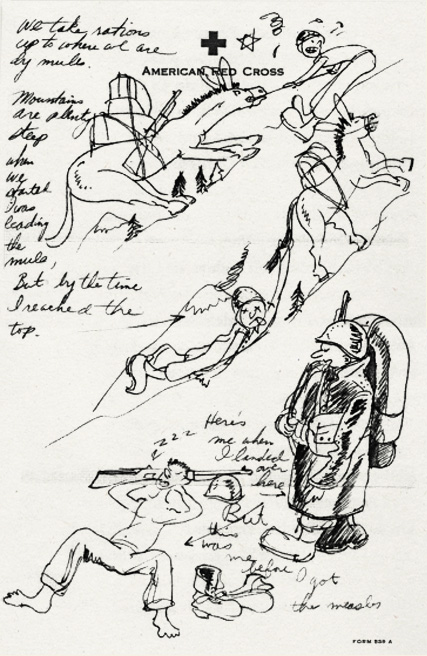

Stanley makes fun of his experience transporting rations and his experience since landing. Letter dated March 26, 1945.

Purple Heart

On May 8, the US celebrated its victory in Europe, called V-E Day. The next day, the Hayamis received a telegram that Stanley had been killed in action on April 23, 1945, in Italy.

He had been shot while administering first aid to two wounded soldiers. For his bravery, he was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart posthumously.

Pvt. Hayami left his covered position and crept toward the wounded men. Despite the hostile machine gun and sniper fire directed at him, he reached the first casualty. Exposing himself in a kneeling position, he administered first aid and then proceeded to another man and rendered first aid without regard for the foe’s heavy fire. While engaged in this act he was mortally wounded. Pvt. Hayami’s unselfish courage under such hazardous combat conditions reflects credit upon the finest traditions of the United States Army.

Stanley with his rifle

Stanley had dreamed of becoming “the best artist in the world.” Killed in combat at the age of 19, he was not able to see his dreams fulfilled, but his drawings and writings have been featured on television, in museums, and online. Through his art he has shared with the world the heart of a young man coming of age at a pivotal time in world history.

Credits

Diary images shown on this page are credited to the Japanese American National Museum (Gift from the estate of Frank Naoichi and Asano Hayami, parents of Stanley Kunio Hayami 95.226 and Gift of Grace S. Koide 2010.4). Photographs are courtesy of the Hayami family and the George and Frank C. Hirahara Collection, Washington State University Libraries Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections.